Roberta McKern

In the East Linn Museum a large, hand-drawn map of Linn County backs a partition of the household room near the rear exit sign.

Most of us would not notice it if our attention were not directed toward it. Compiled in the 1930s, the map depicts landownership. One thing we can trace is the course of the Calapooia River as it travels down between small town, farm and forest platted properties. Several parcels show ownership by banks, the 1930s Great Depression being in full force, resulting in some foreclosures.

The Calapooia rises up near Tidbits Mountain in the extinct volcanic stronghold of the old Cascade Mountains and exits into the Willamette at Albany along the north side of Bryant Park. Along the way it passes through Holley, Crawfordsville, Brownsville and the failed town site of Boston, not far from Shedd.

Lois Robnett Rice, one of the museum’s founders, had a strong interest in the Holley and Crawfordsville areas, for she had descended from one pioneer family and had married into another. The map shows where Robnetts and Rices homesteaded and that interest in the history of the land where she grew up is reflected in the founding of the museum.

Through this area, of course, flowed the Calapooia River, central to the valley it had formed.

On the map, too, can be located the name Philpott. Justin Philpott, a well-known former Holley blacksmith, contributed to Lois Rice’s museum.

Among the Indian artifacts we can find Calapooia Indian points and knives and perhaps scrapers which he found on the family farm or perhaps on the Calapooia gravel bars. Mounted on two pieces of cardboard, they have been worked from agate and jasper and obsidian.

Other artifacts can be seen, too, including mortars and pestles, but we definitely know those identified with Justin Philpott came from the Calapooia. Exactly where many of the other artifacts were found remains uncertain.

The Calapooia Indians are now called Kalapuyans, but here we will stick to the name given to the river in association with them. The Kalapuyans included many other bands who spoke the same language, but in different dialects, suggesting a lengthy period of isolation between the groups. Tualatin, Lukiamute, and Santiam were some of the other Kalapuya bands.

For them, the bulb of the camas lily was a cash crop. Once roasted, it was a staple of their diet, prepared in a variety of ways for winter food and as a trade goods with other Indian groups. We still see clusters of camas blooming as springtime wild flowers, but we don’t often imagine how it may have looked to the first pioneers along the Calapooia who viewed extensive fields of deep indigo blue.

Wheat farmers, the pioneers were attracted by a lack of brush in the camas fields more than by the plants themselves. Not understanding the Indians’ use of seasonal burning of the cleared lands along the Calapooia and foothills, they ploughed under the camas fields to grow grain crops.

Terrible epidemics had decimated the people in the 1830s and 40s, and the Calapooia Indians who remained lacked strength in numbers and were soon removed to reservations.

Along the Calapooia, they left two legacies: patches of hardy camas blooms in spring, and artifacts in some fields and in the river’s gravel bars like those picked up by Justin Philott.

Also, they left paths along the river’s course leading to further reaches upstream allowing for settlement in towns alongside the stream itself and to a crossing of the divide between the Santiam and Calapooia River valleys which abetted the discovery of the Sweet Home valley and the East Linn area.

Eventually, paths became roadways that traveled on up the Calapooia to Tidbits Mountain and the nearby Blue River mining district, where gold was discovered and, in time, the Lucky Boy Mine. People still seek gold in the Calapooia waters, hobbyists using portable sluice boxes.

But most of the gold the settlers along the Calapooia gained came from California, some of it earned by selling wheat flour to mining camps in that state and in southern Oregon.

However, when the first grist mill in Oregon territory located south of Oregon City was built on the Calapooia, the settlers were more interested in survival than sales. Richard C. Finley selected the rapids below Crawfordsville at which to build a small mill initially using burrs (millstones) cut from rock quarried south of Brownsville.

We can think of the Calapooia Valley as being an Eden when the first settlers came. Migrating salmon, lampreys and steelhead teemed in the river, so thick at times of the year it was said a man could walk over them and reach the other bank dry shod.

Migratory wild fowl, too, were so numerous they were beaten with clubs. Some were eaten, and some were fed to hogs. Deer were shot and their smoked hams used in trade.

Eden had to be civilized and grist mills were certain signs of progress.

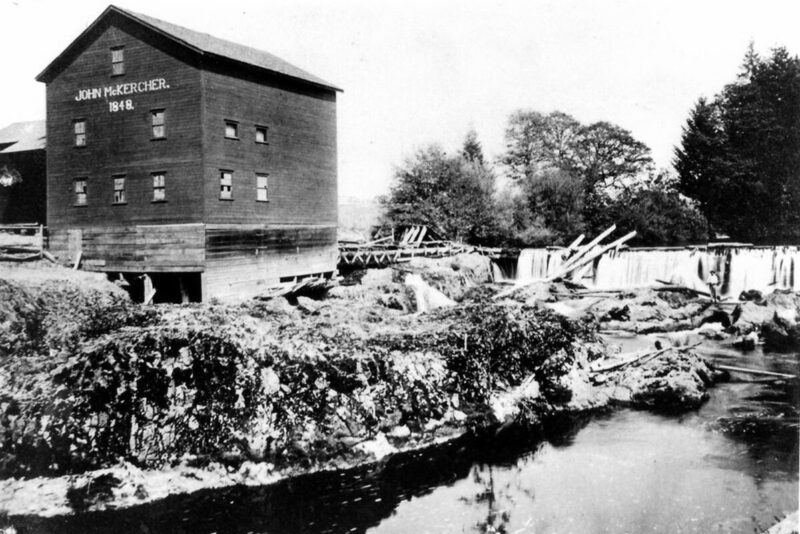

Finley’s first mill, set where McKercher Park is now, washed out in the great flood of 1861-62, but he built a second one, which he later sold to the McKerchers. Richard C. Finley became an entrepreneur who made good use of the Calapooia River.

He owned part interest in one of the first sawmills, an up-and-down rig near Crawfordsville. He also floated hand-hewn beams downstream to a point on the river close to where Shedd would be. There he, in partnership with others, constructed another grist mill.

They also platted a town and named it Boston.

Boston did not flourish as a river town because the north-south railroad headed toward California was built farther to the west, by-passing Boston’s future when the town had barely enough people for a tea party with crumpets. The Boston mill is the only one of the grist mills constructed on the Calapooia River to remain as a historic site.

Brownsville had a grist mill at one time and so did Holley. The best known of those built along the Calapooia was Albany’s Magnolia Flouring Mill owned by the Monteiths and partners.

Brownsville’s most well-known mill wove cloth instead of grinding grain. This was the Eagle Woolen Mill started in the 1860s. It burned with finality in 1955.

It and the McHargue grist mill used water from a mill ditch, parts of which remain running along the ridge behind the town. The mill ditch began a mile and a half east of town where a dam crossed the river, but didn’t entirely impede its flow.

The dam proved to be a very popular swimming hole for generations, but it has now been removed. Like it, however, two places where other mills once used Calapooia water also turned into popular places of recreation, Finley’s mill site at McKercher Park and the confluence of the Calapooia and Willamette River at Albany.

Yes, swimmers still enjoy the sites where these mills once thrived, but the mills disappeared in the 1950s.

The East Linn Museum has two souvenirs of those mill days: the McKercher coin box, battered and worn with use, and a warm, dark red blanket from the Brownsville Woolen Mill. Years ago when the Woolen Mill was dyeing, water from its mill ditch drained into the Calapooia, turning stretches of river water blue, yellow or red.

Calapooia waters powered other mills than those grinding grain for flour. These, starting out with J.C. Finley’s at Crawfordsville, were sawmills.

As timber was cut from one place to the next, sawmills moved upstream, following their sources of supply. In the earlier days of logging, being close to a river became a necessity because logs could be cold decked and then turned loose in a drive down stream. Setting up coffer dams along the river also helped keep the water flowing for such a drive.

We see the current Calapooia as being a smallish, somewhat unimpressive stream, except in flood time. Then it carries along fallen full-grown cottonwood trees and transfers gravel bars downstream.

Apparently, in the past the river was used for log drives down to the greater river highway, the Willamette. However, a proliferation of sawmills along our part of the river generally looked less exciting. One was the Sawyer Mill above Holley. The museum has an ox yoke used to snake logs from the woods on their way to the Sawyer brothers mill.

The coming of log trucks helped end the need for log drives.

For the Calapooia this meant the establishment of Dollar Camp a good distance up the old mining route to the Lucky Boy Mine from Holley. Locations for Robert Dollar’s camp and the plats of timber he owned can be found on the 1930’s map which called the forested areas the Santiam National Forest. Santiam has been replaced by Willamette in these days.

Dollar Camp stood near the Calapooia River. If it drew upon the river’s water, it could have been as ground water from wells. As we know, Dollar Camp lay at the end of a spur railroad running from Sweet Home in the early 1930s. The camp acted as a reloading zone, shipping out logs harvested from the upper Calapooia toward Tidbits Mountain.

It flourished most during the 1940s and 50s, World War II and post-war years. The camp supported a machine shop, housing for employees and among other buildings a cook shack big enough to make use of a lengthy cook stove constructed of welded cast iron sheets. The stove now sits in the museum’s back room for visitors to view.

Dollar Camp has been razed and replanted to Douglas fir and the railroad is completely gone, but some of us at the museum would like to know more about the place.

Although the Calapooia still supplies water for communities whether directly or indirectly when wells pull water from the nearby river, it no longer supplies water to power various mills.

During the 1950s when the South Santiam was turned into a feeder for the reservoirs above Sweet Home, the Calapooia missed having its upper reaches drowned by a dam at Holley. The “damming fever” subsided before then.

The stream, however, has been dammed by agricultural and municipal run-off, and in summer wears many streamers of green algae in its shallow waters. Still, it is considered a wild river and efforts are being made to increase its ability to support a return of fish and other wild life.

In some places beavers have been allowed to construct their dams again.

One thing the river has offered is the treasure of finding semi-precious gemstones in its gravels – agate and jasper and petrified wood, stones like those seen among Justin Philpott’s display of Calapooia Indian artifacts.

At the East Linn Museum, pieces of history regarding the river’s past and the pasts of those who’ve lived along it are the gemstones. To do the Calapooia River better justice, it must be said that the stream, if not clear and blue, does have its times of beauty. Water colorists can particularly appreciate the falls at the McKercher dam site, especially in spring or fall.

We will end our story of the Calapooia River with words from someone who has lived near it and watched children, grandchildren and friends enjoy its wonders through the seasons for over 40 years:

Our River the Calapooia

A gentle, refreshing place for children’s play in summer

Quiet waters for small feet, deep pools for quick dips

Sticks and stones for castles and dams built by active imaginations and willing partners

A place of awe and wonder after fall rains and winter storms

Gentle waters turn grey and angry

Powerful currents eat away dirt banks, falling trees and carrying them to new resting places.

We are only visitors, privileged to share a brief moment in time with this river.

– Glenda Hopkins

The East Linn Museum is more or less open, with the current precautions remembered. Please stay healthy and brighten your day with a visit.