Sean C. Morgan

Of The New Era

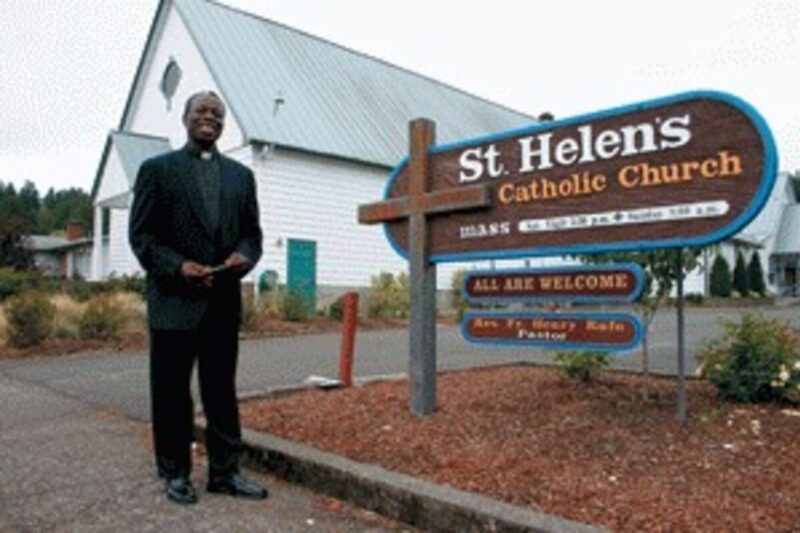

From a continent half a world away, Father Raphael Kyiebiineh is visiting Sweet Home to fill in at St. Helen’s Catholic Church for vacationing Father Henry Rufo.

Kyiebiineh is the pastor in the Funsi Parish in rural northwestern Ghana, and he is looking for support for his parish, which is among the poorest areas of his nation.

Kyiebiineh, 58, is the pastor of a parish covering some 950 square miles with 22 villages, he said. The parish system is not the same in Ghana as it is in the United States. Geographical location dictates where members attend church.

“My parish has a population of about 30,000 people,” he said. “But only 1,000 are Catholics. The rest are Muslims (about 50 percent), a very great Muslim influence, and traditional worshipers who still follow the ways of their grandfathers (traditional African religion).

“The really interesting thing is they are all within my parish, so I am responsible for them.”

As a priest, he is responsible for not only the spiritual but the physical welfare of his parish.

Impoverished parish

“The parish is in a very deprived area of the country,” Kyiebiineh said. “Education, health and infrastructure facilities are almost non-existent. The inhabitants are mainly Sissalas and are mainly subsistence farmers. Millet, maize, yam and groundnuts are mainly grown crops. There are periodical food shortages, especially during the farming season. Unpredictable weather conditions, traditional cultural practices and lack of credit support contribute to low agricultural productivity. There are limited economic opportunities in the area. This forces the youth to out-migrate to the cities for (work).”

The cities are a contrast to this area of Ghana, Kyiebiineh said. “If you go into Accra (the capitol), you think you are in America. The farther (out) you are, the poorer it is.”

The area has an illiteracy rate of about 95 percent, Kyiebiineh said, and about half the population earn less than $1 per week.

Farming is mostly done with hand tools, he said. A few have oxen and plows. During good years, the people may have extra food to sell in a market. Normally, three meals a day is uncommon for adults, preferring to leave breakfast for their children.

The people of the area have no electricity or running water, he said. The church provides drinking water by digging wells for the villages, but they go dry during the dry season. The church has a deep well with a pump for use by the local clinic.

Kyiebiineh must travel 70 miles to the city to get his mail or use an Internet café, and he travels 40 miles to the different villages. The villages are seven to 10 miles apart along poor undeveloped roads, requiring a pickup or other off-road vehicle to travel.

The dropout rate at the junior secondary level is high, Kyiebiineh said. Families often cannot afford to send their children at that level. Vocational and senior secondary schools are not even in the area.

Education is public, but families also pay some money for school, he said. The Catholic church built schools in the area, but until it did, children met for school under trees outside. The church also has a fund for the brightest and neediest students.

Catholic Relief Services provides lunches for school children. Getting more aid from the Catholic church essentially depends on the bishops of his country dealing with the bishops of the United States.

Health facilities are still inadequate, he said. The area has two health centers. One of them is forced to cover about 20 villages. Hospitals are far removed from the area, about 100 kilometers to the closest, and Kyiebiineh provides “ambulance” service, taking patients from the clinic to the distant hospital by pickup.

The clinic’s water supply is the single deep well, Kyiebiineh said. That well was powered by solar panels, but those have failed. It is now powered by a diesel generator at an equivalent price of $4.20 per gallon.

Weekly collections bring in an equivalent of $5. One dollar is the equivalent of about 9,000 “cedis,” the local currency. From that, he must pay for diesel for travel and for the generator; so the generator is only three hours every three days.

Kyiebiineh eats from a garden he keeps at the church.

“So I am appealing for solar panels, so I can put the pump back on solar power,” he said. That would provide water for the clinic, nurses’ quarters and the garden. He estimates the eight panels he needs will cost about $4,000.

While in Sweet Home, he was also seeking funds to help provide education, a laptop computer to help translate the Old Testament and liturgy to Sissalas and cash to repair his broken-down pickup. He prefers a laptop because it is battery-powered – important in an area with unstable power.

The job is difficult, but “that is my work as a priest,” he said. “I have to see to the social needs of the people in my parish. I have to see to their pastoral needs as well.”

His job is to take care of the whole person, he said. “We want everybody at least to live a dignified life. It is for love of my work. That is why we struggle to get funds to help build schools.”

He is able to do the work with the help of friends like those at St. Helen’s and Sweet Home.

“The hardest part is when I have the ideas but I cannot implement it because I lack the funds,” he said. “I have the people, but can’t complete it because of a lack of funds.”

Kyiebiineh came to Sweet Home at the request of Sharon and Skip Malone after they asked when Rufo was planning to take vacation. He is covering the parish through Oct. 5.

He hopes to develop a relationship with the church in Sweet Home, he said. That’s one of the ways he can sustain his ministry in Ghana.

Muslim-Christian relations and evangelism

Kyiebiineh said the relationship between Christians and Muslims in his area is different than other places, where violence breaks out.

“Muslims … in my parish, even if they have feelings against Christians, (the feelings) will not manifest because of what the church has done for them,” Kyiebiineh said. They refer to the church as their government because they have been neglected by the government.

In his diocese, his bishop has appointed a priest who is working on a Muslim-Christian dialogue to show Muslims what Christians are.

There is no open conflict, unlike in Nigeria and other places, he said.

Evangelism is difficult, he said. Christians are a small minority there, and “we have a lot of work to get to the people.”

They see the life of Christians and as “an area of primary evangelism, you talk to the people about God.”

Most of his work focuses on the social aspect though, he said, helping people solve problems.

“We call it the total development of the person,” he said.

Kyiebiineh’s roots

Kyiebiineh’s service as a priest is rooted in his family.

Kyiebiineh was the second of four children. He was educated in Ghana through secondary school.

His father was a “catechist,” a lay person devoted to learning the catechism.

“He was teaching the Word of God already to the people,” Kyiebiineh said. “This came to me that I should be able to save my people.”

The region has two main tribes, he said. The diocese has only two priests out of 90, even now, who are Sissali. “I felt the call, I’ve got to get in there and something for my people, the Sissalis.”

He was ordained in 1977.

Donations

Donations may be made in Father Raphael Kyiebiineh’s name at Washington Mutual Bank in Lebanon. People also may contact the church or Sharon and Skip Malone to help out.