Mona Waibel

Our class of 1948 has always been close, and Bob Furrer was always our No. 1 leader. He was our valedictorian. He was just an amazing guy.

Sadly, Bob passed away March 18, just as I finished this article, so it will all have to be in past tense now.

When Bob was in his teens, his dad supplied logs for the Jones Veneer plant and Bob worked at the Jones Veneer mill in 1949 and 1950.

He was a “mill pond monkey,” cleaning the flotsam on the surface for 65 cents an hour. This was a dirty, smelly job, pulling out chunks of waste wood, raking bark chips off the water’s surface and wheel-barrowing it to the conveyor that sent it to the burner. Sometimes he had to walk on floating pond logs without calk boots. He slipped and fell in the pond. Probably the only thing that was worse was to have fallen into an outhouse hole – when the outhouse was moved on Halloween.

Later, Bob was promoted to “fishtail” sawyer, sawing out bulges, thin spots, and other defects from sheer veneer. You can’t use knotty wood for veneer. During the last month of the summer there was an opening on the “green chain” and he graduated to pulling cut sheets of peeled veneer from the conveyor as it was cut by the clipper.

The clipper fed from one of three stacked trays of continuous-sheet veneer from the peeler. It took a few days to pick up the knack of grabbing a corner of each 4×8-foot sheet of veneer on the conveyor, flip it up in the air and guide the sheet to a perfect landing on a neatly stacked pile behind you. Before pulling the largest sheets you pulled 1- to 3-foot wide sheets. Whew!!

Many of Bob’s high school friends were still around Sweet Home, so he and they did a lot of running around in the summer – swimming, fishing, and going to the coast.

Leo Bennett’s dad operated a Shell service station at Cascadia. During the summer of 1949 he repainted the service station yellow. Leo had acquired an old 1919 Franklin rag-top touring sedan that had been handed down at high school for many years. When the painters finished with the building, Leo asked if they could give his car a shot of paint. They not only painted the exterior surfaces, the wheels and tires, but the interior, including the dashboard, all yellow. This crazy machine ran around all summer, and the paint job was free.

During the summer of 1950, Bob was back at the veneer plant. This time he started as a “barker” at the first station, removing bark from the logs before they were peeled into veneer. This job paid better wages – $1.25 an hour! Here pre-cut 8-foot peeler blocks were hoisted from the mill pond onto the deck and bark was removed by a hand axe. This was heavy work and a bit dangerous, as the heavy axes were sharp and a slip on a log could deflect the axe, cutting your foot or your leg.

All bark and wood debris were shoved into a hole in the deck that fed onto a conveyor belt into the teepee burner. Smoking was not allowed in the mill, and most men chewed Copenhagen – “snuff,” we called it, or Mail Pouch chewing tobacco. Bob decided to give the powerful stuff a try. It made him dizzy.

During the summer of 1950, union organizers came to the plant, hustling all of the workers to join the union. Jones Veneer was not a union shop, although they paid union scale or higher. These organizers usually hit the crew during lunch period, as all were in the pond shack eating lunch. No one appreciated the interruptions as lunch time was only half an hour. These workers walked out on the walkway and walked around the short peelers in the pond and the union shop folks didn’t follow the workers for fear of ending up in the pond!

For part of the summer, Bob worked the swing shift, 4:30 p.m. to 1 a.m. The next morning he stopped at the Shamrock Café for a bite of breakfast and a little “pinball” game on the Bally Feature Machine, which paid off occasionally. One morning while he was at the machine, water was spilled on the glass top and also on the electric system. He got a lot of free breakfasts until the machine was fixed.

Toward the end of summer, Bob’s father needed help with logging so Bob quit the veneer plant and worked with his dad on Green Peter. Most of the salvage logging on Green Peter was from the 1941 forest fire burn.

Bob drove his Ford coupe to the logging site and stayed for an hour every day after quitting time to do fire watch. He helped the tree fallers, Jim Barton and Neil Putnam. Gasoline-powered chain saws were new and the company purchased one of the first Diston chain saws, which had a 6-foot bar and chain with a stinger. It was a heavy two-man machine used for falling large trees.

A few times, the chair saw splattered great gobs of runny pitch and sawdust all over Bob. When bucking a tree, the bar was under stress and you sometimes hung up on a pinched bar and it was precarious to get out of the cut. The caterpillar usually relieved the bind by moving the tree.

Benny Neketin, their cat skinner, yarded the caterpillar with the drum line to the landing. Soon after a log truck backed under the log, he was ready to move out.

The workers did heavy work, arriving at daylight. They were hungry early. Their metal lunch boxes were full – three sandwiches, a thermos of milk, a pie, an apple and fried chicken to last through the long day. Their first meal was eaten about 10 a.m., and they quit working at 5:30 p.m.

After Bob finished fire watch, he usually jumped in the river to cool off. Most loggers rode to the job and back in a crummy, because they would fall asleep soon after sitting down in the truck.

Bob spent every summer logging with his dad and learned more about the business. The next summer they logged up the Calapooia River, just south of Holley until the Fourth of July, when the woods were closed because of fire danger.

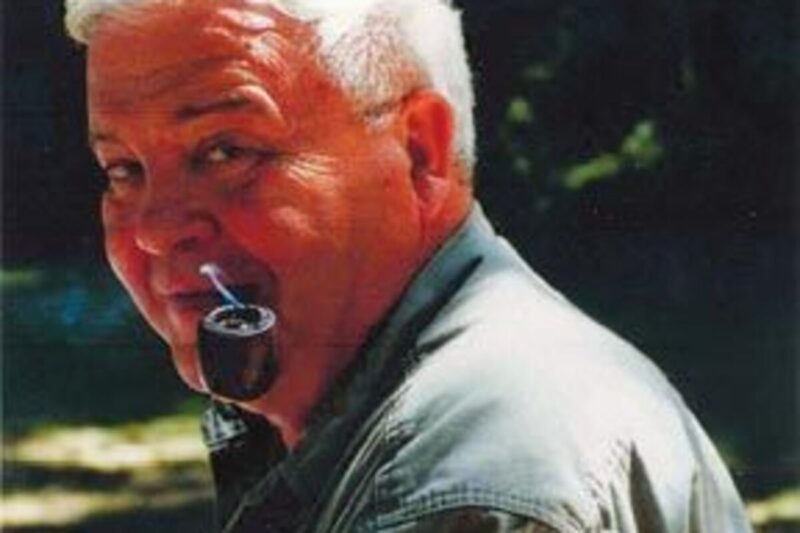

Bob Furrer was one of the most intelligent people I’ve ever known.

We all knew he would do well in life. He was a brilliant architecture student at the University of Oregon, graduating with honors, and pursuing a great career. He was commissioned in what was then the U.S. Army Air Force, having attended school through the ROTC program. He was commissioned as a 2nd lieutenant and served as a pilot in Korea.

After the Korean War, Bob returned to the U of O, where he finished his architectural degree and then worked as a professional planner.

Bob married Victoria Valentine in 1964. They later divorced and in 1985 he married Beth (Church) Ameling.

At that time he had been working for a couple of years in Kuwait and Beth joined him there, where he worked in the Ministry of Public Works until June 1990.

Bob was offered a job and was told this area had “no problems, just differences.”

He was offered an awesome salary, and was told he would have the staff he needed. He was in charge of the power plant, and all other systems.

Bob was no dummy, and he left in 1990, when it was no longer safe – the perfect time to make an exit.

They returned to Lake Oswego and enjoyed many years of world travel. He was active with the Air Force Association, becoming State President in ’93-94.

He was also Past Commander of the Springfield branch of the Military Order. He devoted time to his neighborhood group, Greenridge Townhomes Home-owners Association.

Bob liked to e-mail and we kept in touch. He visited Sweet Home from time to time, especially for class reunions; he enjoyed seeing his old friends and he hung out with his college buddies whenever he could.

Bob enjoyed writing and has published several books. He produced an incredible story about his time in Kuwait.

Bob is survived by his wife, Beth; children Mike of Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, Michelle Shaw of Phoenix, Ariz., Melanie Furrer of Las Vegas, Nev.; stepdaughters Nanci Munroe of Keaau, Hawaii, Carol Dietz of Windsor, Colo., and Ellen Garber of Tucson, Ariz.; and six grandchildren.

Although this was not intended to be an obituary, I’ll add that a graveside service with military honors was held March 21 at Willamette National Cemetery in Portland.