Sean C. Morgan

The City of Sweet Home estimates that up to half of the water it produces is leaking out of the system.

Under a contract with the city, American Leak Detection is locating and compiling a list of leaks in Sweet Home’s water distribution system.

The company went to work on Nov. 13 and will continue for the next week or two. The contractor uses a listening device to hear, locate and evaluate the size of the leaks.

“He’ll go to every meter and listen, and he’ll go to every valve and listen,” said Public Works Director Greg Springman. The technology can pick up leaks two blocks away, and based on the detector’s experience, he can use the noise and volume to pinpoint the leak.

Through the first week, ALD located 32 leaks, Springman said. Among those, five were in water mains, while 27 were in the services, between the mains and meters.

“What happens is they don’t show themselves, sometimes,” Springman said. The leak bores through the ground and hits a storm drain then flows into the river.

Leaks also can flow into sewer lines, contributing to inflow and infiltration. I&I is water that leaks into the sewer system through deteriorating pipes, primarily groundwater from heavy rain storms, potentially overloading the wastewater treatment plant, causing a bypass of untreated wastewater into the river.

The city has been addressing high levels of I&I for the past two decades in four sewer line replacement and rehabilitation projects.

“I’ve done enough of this in my career, (to know) you have to go systematically,” Springman said. After gathering all of the information, “you have to have an action plan to address leaks. It’ll take time.”

“We are putting together a construction crew internally,” he said.

The leaks will be prioritized, and the team will make repairs one by one, Springman said. “The more they work together, they’ll get more efficient.”

The team will work together about once a week, he said. Generally, it will be able to deal with about one leak per week, and “that’s pushing” because the staff members have other projects.

“We’re going to have to take this in-house,” he said, because the city doesn’t have the funds for a contractor.

Having recently ordered and received new equipment, the city has better options for repairing leaks than have been available in the past, Springman said. Instead of digging a trench, the crew can dig holes at each end of a service line and pull the new pipe through.

The city will need to wait for the final report before prioritizing leak repairs, Springman said. In the case of a street with multiple leaks and an old line, the line will move to the top of the city’s five-year capital plan.

In those cases, the city can make temporary replacements and repairs, he said.

The city recently eliminated one leak, taking offline the oldest reservoir of three located off 10th Avenue. The reservoir was leaking 10 gallons per minute, more than 14,000 gallons per day.

“That’s a drop in the bucket,” Springman said. “We’ll be doing a lot more repairs.”

Most likely, Springman said, the water loss is through numerous smaller leaks rather than large leaks.

City staff have isolated and repaired several other leaks, including one losing water at a rate of 20 gallons per minute.

At the rate ALD was locating leaks in the first week, the city would have more than 100 leaks, Springman said. The city has approximately 54 miles of pipe – or 285,000 feet.

The city estimates the amount of water it is losing by comparing how much water the Water Treatment Plant produces and how much is metered.

The Treatment Plant produces roughly 1 million gallons per day.

There should always be a gap between the two amounts, Springman said. Some use, like fire hydrants, is not shown in meters.

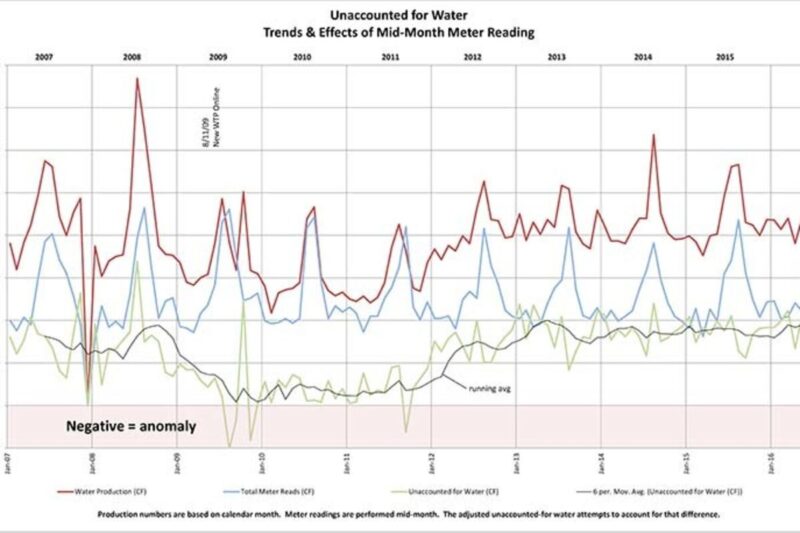

Historical data show that Sweet Home had a gap prior to the construction of the new Water Treatment Plant in 2010. That gap closed substantially after the plant went online.

The gap began growing substantially again during 2012 and roughly reached its current levels during 2013.

The data show lags between production and metered usage because the city produces water and stores water in reservoirs prior to sending it through customers’ meters.