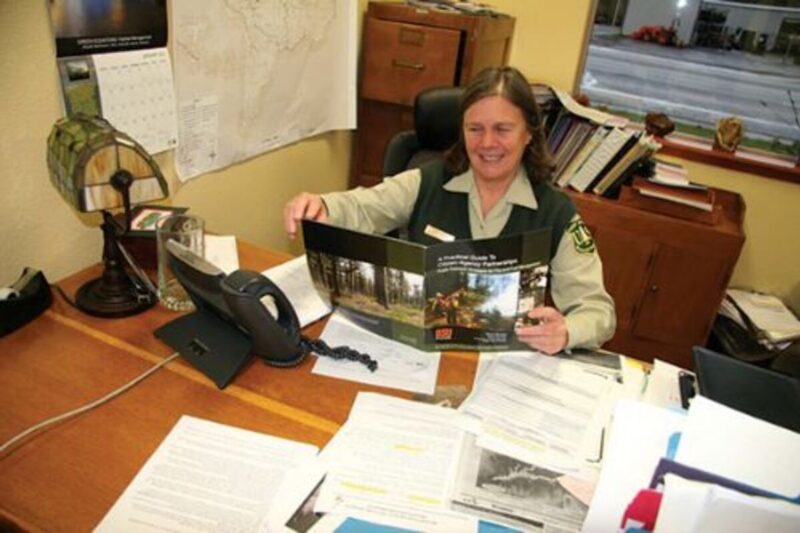

Scott Swanson

Nine months into her tenure as District Ranger in Sweet Home’s U.S. Forest Service headquarters, Cindy Glick has identified two big goals: help people use the forest and figuring out how to use the forest to help people.

Glick, who took over leadership of the Sweet Home Ranger District on April 11, 2011, has a background in forestry, recreation, fire, range and environmental education after serving in the Siuslaw, Deschutes, Ochoco and Malheur national forests in Oregon – the latter her last stop as acting district ranger for the Prairie City Ranger District.

She said her goal is to preserve and create forest-related jobs in local communities, a task that reflects goal s she said have been set down USFS Chief Forester Tom Tidwell.

“He wants us to help socially disadvantaged people, have higher standards of customer service and improve workforce diversity,” she said, noting that the retirement of many veterans and the newcomers taking their places offers an opportunity to accomplish the latter.

“He wants us to be a premier organization, so we are open, responsible, collaborative, transparent and highly effective in pursuing our mission of serving the public and caring for the land. That leads to a very motivated workforce that’s engaged and empowered to succeed.”

So what does that mean on the ground in the Willamette National Forest, particularly Sweet Home?

Glick said her boss, Forest Supervisor Meg Mitchell, believes it means caring for the land but valuing the contributions and services of local communities by providing jobs and opportunities for them to engage with the forest –particularly the young people. She said it also means listening to local residents and to Forest Service employees’ opinions – “listen and implement everybody’s ideas as much as possible.

“To tell you the truth, I’ve never seen such wonderful goals,” Glick said, chuckling delightedly. “I describe it as Nirvana-land. That might be a little out here for people in Sweet Home, but it’s a dream job. It’s a different forest over here, different people, different goals. After 20 years in one place, I wanted to work on some other issues.”

She said she’s particularly convinced that the Forest Service needs to listen to people – particularly those who think outside the box.

“I’ve learned a lot in Sisters and in central Oregon about working with the public,” she said.

She noted that a Jan. 30 field trip to the Toll Joe and the Cool Soda areas, which include a mixture of habitat that the Forest Service is trying to decide what to do with, is a good example of that effort.

“We want to get public input,” Glick said. “We want to hear from people with learning and innovation from years of experience working with this forest, with different expertise in wildlife and hydrology and things like that, and figure out how best to deal with this. I can’t guarantee it won’t get appealed, but we’ll get their ideas on the table.”

A primary goal is to figure out how to get people into the national forest to enjoy it and how it can be managed to help local communities, including Sweet Home.

“Sweet Home is the most underutilized district in the Willamette National Forest,” she said. “That’s peculiar to me because it’s at the lowest elevation, it has hundreds of miles of trails and many campgrounds.”

She’s engaged the services of a consultant, Emily Jane Davis of the University of Oregon, who specializes in working with rural communities, which have suffered downturns in the timber industry on public lands, to develop recreation and tourism.

Davis, who last year earned her Ph.D. in human geography from the University of British Columbia, works in the Ecosystem Workforce Program, which was founded in 1994 to support the development of a high-skill, high-wage ecosystem management industry in the Pacific Northwest.

Davis, along with Forest Service staffers and representatives from other government forest and parks agencies and Linn County Parks Director Brian Carroll, and Sweet Home Economic Development Director Brian Hoffmann, have been meeting to discuss how to develop tourism opportunities in the forest and what it will take to get private timberland owners to buy into ways to improve forest uses.

“We’re working with Cascade Timber Consulting to try to figure out how we can work together to provide public good,” Glick said.

She sees a need for cooperation between CTC and other landowners, whose lands intersect the national forest in a checkerboard fashion, in fire prevention, land stewardship and recreational uses.

“We want to help private timber companies get some revenue, money streams, for doing things on their lands that would help the public – improve water quantity and quality, fish habitat, recreational opportunities for the public and things that we can do to foster elk habitat for hunting.”

She said the term used for that public-private cooperative model is the “all-lands approach” and the Forest Service is already working with CTC on one project in the Soda Fork and Sheep Creek area.

“We’re trying to figure out what the opportunities might be,” she said. “It’s learning and innovation. We’re just working together with our neighbors. It’s a big journey we’re embarking on, but we’re going to try it.”

Another of Glick’s interests is to find more ways for community members to make a living in the forest. She said she’s interested in finding ways to use more hemlock and white fir, as well as smaller trees, for such products as animal bedding (shavings), firewood, or material for plants such as the pellet plant in Brownsville.

“Maybe they’d want to consider whitewood,” she said. She also is interested in whether the local forest could produce fuel for biorefineries such as the one constructed by ZeaChem in Boardman.

“There’s lots of other places where they’ve done it,” Glick said. “I just want to look locally to see if there are niches suitable for some of those waste products that are not being utilized.”

Also on her mind are “special” forest products such as mushrooms, boughs, salal and bear grass, which are renewable resources. Such are already harvested in the Sweet Home District, but Glick said her staff has bigger ideas.

“We’re thinking that we could manage that program in a more effective way to provide more opportunities for people to create jobs, but also administer that use,” she said, noting that her staff is talking with CTC to see how that company manages the thousands of acres in the area owned by the Hill family.

She said stewardship contracts or agreements are one of the “new tools in our tool kit” that may make it possible for such economic development.

“A shed that buys floral products or mushrooms, if we could guarantee some sort of supply, maybe there would be more stability so we could offer family-wage jobs to people,” Glick said. “I don’t know, but we’re seeing if that’s a possibility. Why can’t we develop that entrepreneurial ability? We can manage timber sales. Why can’t we manage this type of thing?”

She’s also investigating whether local forest landowners could reap biodiversity or carbon sequestration credits for the trees they grow.

“There’s tons of others – recreation, tourism, planting trees in riparian areas – we can build the local economy on taking care of the forest, private contractors who specialize in taking care of the land.”

It’s going to take time, but Glick says she has it.

“I plan to be here a while,” she said. “I hope to see those goals through.”