Scott Swanson

Of The New Era

Paul Mosqueda had been gone from Sweet Home a long time when he decided it was time to come back.

Mosqueda, 62, now of Round Rock, Texas ? near Austin, spent much of his childhood living in town with his parents, who were both American Indians.

“My earliest memory is seeing my mother working as a civil defense lookout during World War II,” he said during a recent visit, which included a stop at The New Era to look for some pictures of his family taken 50 years ago during Frontier Days celebration in the 1955 and published in local newspapers. “She had on her Indian headband and braids and she was looking through binoculars.”

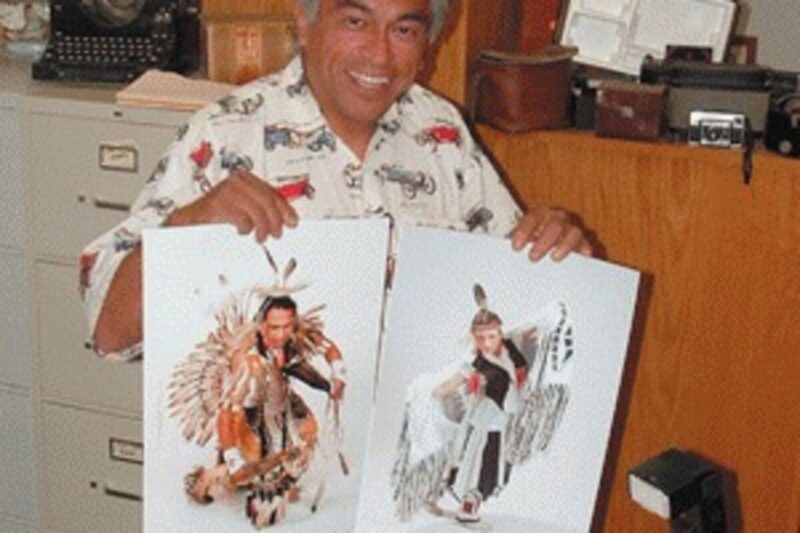

He’s spent most of his adult life as a musician and photographer. He currently operates a portrait and event photography business in Texas.

Mosqueda was born April 21, 1943 in Langmack Hospital ? what is now the Lebanon Public Library. His parents were Nicholas Mosqueda, a Rockyboy Cree from St. Ignatius, Mont., and Bertha Cree Mosqueda, a Yakima Indian from Washington. The Mosquedas lived north of where White’s Electronics is, near the river, Paul Mosqueda said.

Nicholas Mosqueda started out as a logger, then became a mechanic for Abco Parts and Machine, “located next to the old Richfield Service Station on the main drag here in town,” Paul Mosqueda said.

Later, Nicholas became an Arthur Murray Dance instructor, which, Mosqueda said, led to the eventual breakup of his parents’ marriage.

“Dad tuaght me a real strong work ethic and my mother taught me a love for God,” he said.

Mosqueda and his three sisters and two brothers attended a two-room school on the southeast corner of the current Sunnyside School property, he said. When he was in fifth grade, they moved to the new Sunnyside School.

He later attended Sweet Home Junior High, where his teacher, Mr. McCauliffe, urged him to run for student body president. He did and won, he said.

“I was shy and I didn’t think I spoke well,” Mosqueda remembered. “He took the lid off things.”

He said that he has a lot of good memories about Sweet Home from those days.

“We used to hike along the river, but Foster Reservoir is there now,” he said. “White’s Electronics used to be Riddlings Farm. My job used to be to go over there, try to avoid the mule, and get a gallon jug of milk and put it in the refrigerator.”

He said he remembers when the movie “The Ten Commandments” arrived in town “they let us out of school early to go watch it at the Roxy Theater.”

“I saw my first TV in the window of Epps Furniture,” Mosqueda recalled.

He later attended Union High School in Sweet Home, but life was unraveling at home and “I kind of lost focus as things went downhill,” he said.

His mother took the family and left Sweet Home when Mosqueda was a freshman. The family sought work in the fields as migrants and followed the crops, living in migrant worker shacks.

“We did everything from picking strawberries, wild blackberries, huckleberries, hoeing asparagus, harvesting peas, harvesting potatoes,” he said. “In the winter we went back to the (Yakima Valley) reservation.”

Mosqueda later earned a two-year degree from Bacone College in Oklahoma, a school for Native American pre-ministry students in Muskogee, Okla.

During the 1960s and ’70s he performed with a variety of bands and did some stand-up comedy. Along the way his first marriage ended in divorce and, when he was 23, he met his current wife Beverly. He has six sons, two from his first marriage and four with Beverly.

He started a janitorial business near Houston in the late 1970s, then became a financial adviser to Indian tribe members in the late 1980s. He then founded his Golden Moments photography business, which specializes in Indian photos.

Mosqueda said it was good to return to Sweet Home and see some of the old landmarks.

“There’s a memory behind every turn,” he said. “Most of them are pleasant. I realize the impact that the people of this community had on me and on my family.”

His teachers, whom he can still name, were particularly influential, he said.

“At every stage of life, when I needed important direction, a school teacher was there,” Mosqueda said.

“I still see the same heart of people here. When I asked directions (earlier in the day he was in town), someone came running after me and said they’d given me the wrong directions.

“When they shake your hand, you can see their heart on their sleeve.”