Sean C. Morgan

Of The New Era

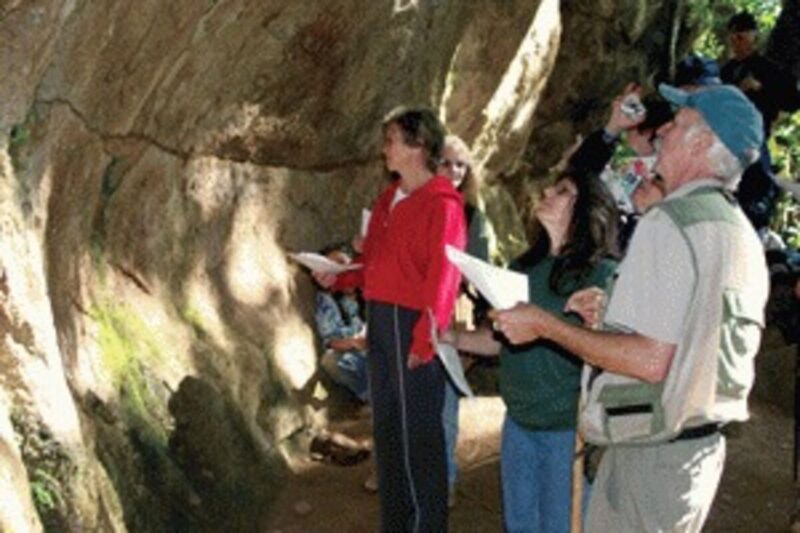

During his final Heritage Hike of the summer, Sweet Home Ranger District Archaeologist Tony Farque painted a vivid picture of a bustling Native American society in the foothills east of Sweet Home.

The woods were like a shopping and industrial center for Indians from the Calapooia and Molalla tribes, where they could find anything they needed to survive – bark from this tree, wood from that tree, salmon from the rivers and berries from this plant or that.

Farque hosted a group of a dozen visitors from across the mid-Valley on the hike, held on Sept. 21, to Cascadia Cave, located on private land north of Cascadia State Park.

Beginning at the park, Farque explained that the property has been used for thousands of years before the European settlers found it and its mineral water, called “stinky water.” Europeans began to come from the east to bathe in the mud and drink the stinky water, claiming that it cured what ailed them.

Farque figures that just leaving the industrialized areas of the east was healthier for the travelers.

George Geisendorfer built a hotel, operating from 1880 to 1917, on the land, taking advantage of the mineral springs, which are now capped because arsenic has been found in the water. A 1910 photo shows a two-story structure during a time when up to 3,000 visitors would attend croquet tournaments on Saturdays.

Farque has been talking with the Brownsville Croquet Club about reviving the tournaments as the Geisendorfer Invitational.

The hotel fell apart and was eventually burned down, Farque said. Long before, Cascadia State Park was the home of many Indian groups, where Calapooia lands below gave way to Molalla lands in the mountains.

Indians would go into the mountains to trade, hunt, pick berries, find medicine and socialize, he said. The main trail through the mountains ran east through this river valley, the South Santiam, an area that was “not fit for roads.”

The trail ran along the north side of the river, Farque said, and the country looked much like Cascadia Park looks today. “This country looked open.”

The Indians, with their fire, had burned the countryside off, keeping the underbrush down and allowing grasses and berries to grow, he said. “We’re trying to reintroduce fire as much as possible.”

But scientists get in the way, he said, because they have taken the cultural components out of their reconstruction efforts.

“We’re walking through the tribal shopping mall,” Farque said as he led his group onto the trail east of the park. Everything the Indians needed was there – food, medicine, resources to make items they needed. It has huckleberries, edible fern, blackberries, the Oregon grape and more for food. Ocean spray, another plant, was useful for making digging tools. He pointed out small trees that were useful for making arrows, with their straight light wood. Yew wood, which also grows in the area, was used for bows.

“The moss is good for sleeping on, bandaging,” he said. Wild rose gave them vitamins by using rose hips in drinks and soups.

During the winter, “you can’t go to the store,” Farque said. “You have to have your food put up. Everybody worked all the time.”

Protein delivered itself up the river every year in the form of salmon, Farque said. Along the banks of the South Santiam, the Indians would coral the fish into cedar weirs. They would spear the fish, and then send them up the steep banks where the fish were preserved by drying, smoking and being wrapped in bark.

The fish could then be transported down the river by canoe to those who were preparing for the winter. The meat could also be taken out on the trail and traded as far away as Oregon City.

The trail winds its way through an old forest, with giant trees more than 700 years old and the oldest among them reaching up to 1,200 years.

The trees, with their extremely thick bark, are fireproof, Farque said. The smaller trees that grow up around them are like weeds, coming in and stealing the nutrients. Fire helped keep those away without affecting the large trees.

Among the trees in the area are the western red cedar, the most important to the tribes of the area, Farque said. From it, they made waterproof capes, baskets, boxes and canoes. It was easy to shape with stone ax heads, and it splits straight.

The Indians would cut away 4-foot sheets of bark for use in some items. To make a canoe, Farque believes, they would climb a tree and split it near the top. The wind would blow it down straight and true and leave logs on the ground.

The cedar also has a lot of oil, he said, and the Native Americans would use it in ceremonial fires for the explosions of sparks it would give off.

The trail soon meanders onto Hill family property managed by Cascade Timber Consulting.

The Forest Service leads hikes through the land to Cascadia Cave by permission, he said. They like the administrative presence on the land to help reduce vandalism and theft “because we are walking over ancestral ground.”

The Hill family has protected this particular property, and groups are working on getting it into the public domain, Farque said.

The trail leads past the last of the old meadows, Farque said. The other open meadows on the bench have been overgrown. This particular meadow was used as a Depression-era camp. Old pottery, bottles, stoneware and more can be found in the area.

A small overhang and cave along the way provided shelter and protection from the elements, he said.

A little way past the small cave is what is called Cascadia Cave, a large overhang and cliff face covered with petroglyphs.

“I love this spot,” Farque said. Nowhere else in the Northwest are there so many petroglyphs as Cascadia Cave.

Farque warns visitors not to touch the wall, he said, because the oils from human hands can put the art at risk as it reacts with the consolidated ash flows that make up the wall.

It has been an area used by people hunting and living in the area for 9,000 years, Farque said. “The rock art is an indication that this was a place used for ceremonial purpose, religious purposes.”

It is inside the Calapooia-Molalla transition area, he said. It is along the main east-west path through the mountains and one-quarter mile from the north-south route through the mountains. At the same time, it is also near the camas prairies and food processing areas used by the local Indians.

The rock art itself has been documented at different times, and Farque has maps of the art he hands out on such hikes, which he also hosts for school groups. Some of the mapped art is hardly visible, while now and then someone spots something new.

The art is visible to different degrees throughout the year as the sun changes its position in the sky, Farque said. The best light for seeing the art is in February, he said.

For more information about Heritage Hikes or Cascadia Cave, contact the Sweet Home Ranger District at 367-5168. The district also offers other hikes in the Sweet Home area.