Roberta McKern

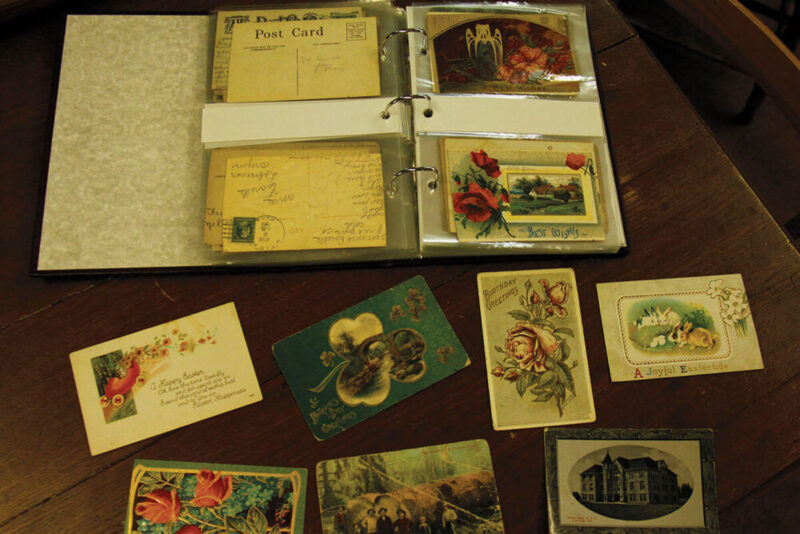

Not long ago, a number of colorful picture postcards at the East Linn Museum drew attention as they were placed in new albums with plastic sheaths, which allow both sides to be seen. What have we here?

Some postmarks went back to 1908. Many were addressed to Mr. and Mrs. Gerry Coryell, others to Noma Ireland. The cards arrived in a trunk donated by the Ireland family. It was stored in the museum’s attic for years before being opened, leading to the postcards’ discovery.

Here, we’re looking primarily at the cards themselves. If a picture’s worth 1,000 words, however, just a few may not suffice. But we’ll give it a try, anyway.

Colorful picture postcards have been around since about the 1870s in the United States. Some European countries developed them sooner, and, for many, postcards printed in Europe were sold in the United States. Postage for sending American cards remained at one cent within the U.S., two cents to a foreign country.

Greeting cards set the way for postcards in the 1840s. England was great at offering greetings that came by mail and in envelopes, and the later pictures on postcards emulate those on greeting cards often made in England and sold here. It took major aspects to get the postcard industry off and running: literacy, improved printing techniques and a good postal system.

No matter the image on a picture postcard, a sender must be able to list an address, and it’s polite to include a signature. A postmark will reveal where and when it came from. Most of the cards we examined were written in pencil and difficult to read.

Of course, the images were meant to expand awareness beyond the limitations of a few written words in the small place left for messages on the back. And what images! Nearly everything. But because postcards traveled through different hands before reaching their destinations, lewd, crude or nude must be eschewed. This gives many a definite decorum.

Many of us think of postcards as souvenirs of places we or others have been. People going to the coast send pictures of oceans back to inland towns. Those taking mountain trips direct scenic views of snowy peaks from the opposite direction. Thus, we can examine Monterey Beach scenes on a card from Newport, and the Three Sisters on the other hand.

We all know the jargon of postcards: “I’m well, having a good time, nice weather, wish you were here,” although many messages on the ones in the museum ask, “When will you write? When will you come see me?” However, one of a suspended footbridge outside Elgin, Illinois, lets its writer marvel at how impressed he was. To his Uncle Jerry Coryell, the nephew wrote, “Here is the swinging bridge at the cemetry [cemetery]. It crosses a long hollow. If you was in the center … you would think it was going out from under your feet.”

The cards are often addressed to Jerry and Seenith Coryell or to Noma Ireland. A photo with the cards shows the Coryells to be older, and according to another photo of their headstone, Seenith Coryell lived from 1860 to 1927. Jerry Coryell was born in 1858. His death date isn’t finished, but the picture includes a fresh grave covered in flowers.

Noma Ireland is first addressed as “Miss,” but it appears that she married and moved to Wasco, Oregon, according to address changes, when she became Mrs. Noma Jackson. Otherwise, she lived in Dayton and Lebanon. Since some cards are addressed to Mrs. Seenith Coryell in Utica, Kansas, we suspect she saved them, as did Noma. This included when she visited Kansas and heard from back home.

Addresses generally list only the names of towns and states. The Coryells’ is Lebanon, Oregon, with a small “Rt. 2” appearing to the left near the bottom of the card’s address space. Postmasters and mail carriers had to know where their clients lived. This reflects how small Lebanon and Dayton, for instance, were at the time. And who visited? When Seenith was in Kansas, the address still remained the town, Utica, and state, Kansas. Had she lived there?

Many cards received by the Coryells feature bright, artistically lovely illustrations of flowers. Many also are greeting and birthday cards, with the holiday well-represented. Thus, we get into the language of flowers, an aspect popular in the late 1800s and earlier 1900s.

What can beat fresh flowers for beauty? They have long been appreciated and used as symbols variously of purity, piety, love, thoughtfulness and all sorts of emotions. White lilies, purity and piety, for example. And daisies, signs of love, “He loves me, he loves me not,” we say while plucking daisy petals. Or, conversely, “Daisies don’t tell.” Pensive pansies stand for thoughtfulness, and the blue forget-me-not’s very name speaks for itself. These are the most often seen flowers on the Coryells’ cards.

Roses, too, proliferate. There’s always the romance of the rose. A Valentine card sent to Noma features a winged cupid figure wearing a sleeveless shirt to the knees. It rides the stems of a pink-daisy bouquet. Two red hearts dangle from the bridle leading to the flowers’ ball. Not postmarked, the card asks, “How many valentines did you get, let me know,” without punctuation.

Many of the greeting postcards are scenic. New Year’s doesn’t seem capable of passing without a sunset. Nor Easter without a bunny, ducklings or chicks. And Thanksgiving without turkey? Hard to contemplate. Things haven’t changed. In one 1915 Thanksgiving card we see the corn in shocks and pumpkins in a field as a pilgrim armed with a blunderbuss approaches a turkey hiding behind the corn.

Once in a while, a pun creeps in, as on cards sent to Seenith. In one, a workman falls from a ladder. His derby flies behind him, and a can of red paint spills in the air. He lands on the back of a distraught bricklayer losing his cargo. The caption: “I stopped on my way down.”

Another depicts a lively mustached spoon bending and holding his hand out to a pretty Gibson girl in a pink dress. A dandy, he wears spats over his shoes. “How’d you like to spoon with me?” he asks.

Two of Noma’s racier postcards feature a stylish Gibson girl and a gentleman. On one, the girl sits by a bottle atop a small table. Her mouth is open, ready to take whatever the gentleman’s holding in a spoon as his other hand holds her shoulder. “I’ll have to take my medicine,” she says.

In the second retouched 1909 photo, a fellow peers from around a tree at a pretty girl in the summer landscape. “Answer please, please hurry,” she says immodestly. “Don’t you make me worry. Tell me, could you learn to love a girl like me?” These cards are fresh for the times.

Another racy illustration shows a beach scene: a fully dressed girl in a boater hat, long blue skirt, white shirt with a red belt at her waist, and red tie around her neck. She sports a pink parasol. Her swain sits at her feet, his back to us, in his bathing attire: brown trunks and a gold and purplish brown singlet. Other people are visible along the ocean’s edge in the background, including a woman in a hat and long dress, bearing her own parasol. An idealized beach scene. He is the bathing beauty.

Five cards feature educational buildings. One from Portland calls Noma’s attention to the new multistoried Behnke-Walker Business College, established in 1902. Its blue typewritten print assures her, “It is your best school.” The building is said to have a capacity of 500 to 1,000 students. There are also photos of Mechanical Hall O.A.C. (OSU), Corvallis and Eaton Hall at Willamette University in Salem.

Fewer logging pictures show up from our area than we might expect. In one, two loggers pose with a “Big Cedar,” a large wedge cut from it. One lies in the cut with his axe in front of him. The other stands beside him on his springboard, his axe resting against the tree. Their long crosscut saw stretches across the projecting springboards to illustrate the tree’s width.

The second photo depicts a downed double-trunked conifer, where two trees fused and grew together. A crew of loggers and a boy of around 11 or 12 pose in front of it. Obviously, it was hard work.

One card draws attention to its postmark because the date is Nov. 4, 1918, and the mark contains the admonition, “Food will win the war. Don’t waste.” (World War I ended seven days later.)

All in all, nearly 200 postcards comprise the collection. Later ones go to the 1940s but weren’t sent, so no messages or postmarks explain more about them. Many are souvenirs from California. Considering the very artistic paintings of flowers and landscapes on many of the earlier postcards, we can understand why they were saved. The older ones are quite collectible today, a continuation from the past when postcards were expected to be kept as reminders of friends and family and their love and affection.

An 1898 Sears Roebuck catalog lists souvenir postcard albums. A not-too-fancy small one holding 24 could be had for 30 cents. Their prices and quality covered a range up to the most expensive ones bound in black-walrus-grained leather, which held 304, or four to a page. Its price: $2.70.

The East Linn Museum does have some postcards for sale, three for $1. Many feature Oregon covered bridges, but selections are limited, and none are as artistic and pretty as the floral and scenic ones received between 1908 to 1918, at least by the Coryells and Noma Ireland. We don’t know how much they cost, and no photos appear on them.

The museum is getting desperate regarding a lack of volunteers. One suggestion was to be open only two days a week. The direst prediction: We’ll have to close. Age and infirmities are taking a toll on the best volunteers, and each of us is of the best.

It’s not hard to be a volunteer. No special knowledge is required. There are no entrance exams. Simply be willing to spend part of a day or two a month greeting visitors, and keep the museum open. Anyone of a reasonable age and nature may apply. And don’t underrate your knowledge or skills. The museum can be an inspiration.