Sean C. Morgan

Of The New Era

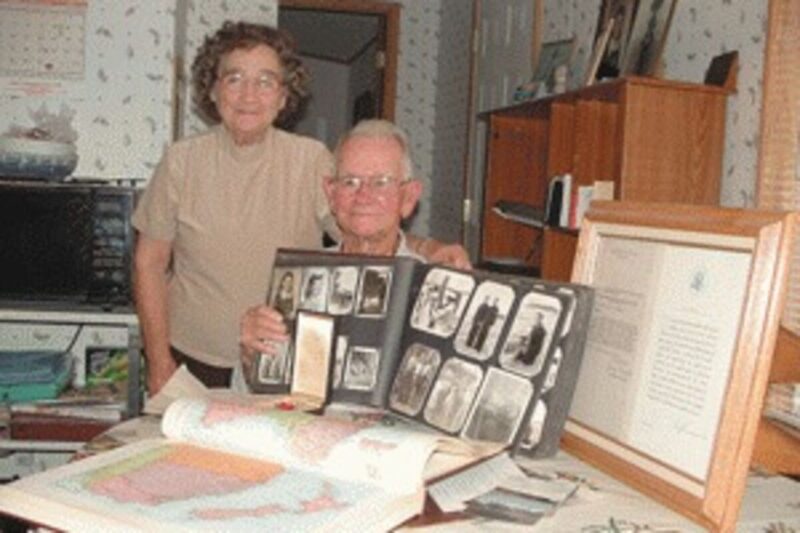

Dave Bennett doesn?t think of himself as a hero.

He just did his job, he said.

In doing that job, he went from being a target for court martial to earning a medal.

Bennett?s military career took him to an Australian lumber yard to shipboard battle and to the kamikaze attack on his ship that led to his Bronze Star.

Bennett, 82, grew up in Oklahoma and graduated from high school in 1942. He started college but learned he would only get a six-month deferment.

?They wouldn?t let me finish my schooling, so I went in(to the military),?Bennett said. He said didn?t know at the time that the six-month deferments were standard for school and could be extended.

He signed on with the Navy and went to basic training in San Diego on Feb. 16, 1943. He was stationed at Brisbane, Australia.

?I started right off working in the lumber yard, about four acres of lumber that was just criss-crossed,? Bennett said. It took about three months to straighten it up. The lumber was used for a variety of military buildings.

Bennett wanted to get his job done and go home to Wilda, who would become his wife of 61 years. He began looking for a way onto a ship. After serving a period on ship, he figured, he would be able to go home.

He worked out a deal with an officer who wanted some wood, and he was soon moved to the electric shop.

?I worked there at the base about six more months,? Bennett said, before he was able to convince his commanding officer to let him go. He went aboard submarine chaser 699 (SC699) in spring 1944 as a third-class electrician?s mate, responsible for care of the electronics, repair and maintenance.

?I broke all the regs in the book because I was never a fireman, I never served KP (kitchen police),? Bennett said. Normally, electricians serve as firemen first, and everyone was required to pull KP.

?Right before I left the ship, an officer I had trouble with, he went through my record and he says, ?Bennett never served no KP,?? Bennett recalled. ?He said ?everybody serves KP?? and took Bennett to the skipper, Capt. Orville Wahrenbrock.

The skipper asked the officer who did all of the electrical work and dismissed the complaint.

SC699 had a crew of 24 men and three officers. It made two landings with Bennett aboard.

?I was a loader on the big gun,?a twin 45-mm deck gun, Bennett said.

The second landing, part of the American island-hopping campaign, at Wadke, New Guinea, ended with a terrifying attack on SC699.

?We were knocking the planes out,?Bennett said. ?I was standing by the gunner.?

His ship was firing over the flag ship, which carried Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kincaid. The crew saw a Japanese plane come in low over the flag ship, a four-stack destroyer, also called a ?tin can.?

SC699 was ordered to stop firing because the plane was so low over the flagship.

?I just said, ?dear Lord, this is it,?? Bennett said. As the plane, with its 54-foot wingspan, aimed at the 110-foot SC699, the 20-mm gunner, a man named Bill, opened fire. His shot hit the pilot and caused a wing to dip.

The ship escaped being hit by the entire plane, and Bill saved the lives of the crew, Bennett said. The Japanese plane clipped the ship, but most of it went over the ship.

The captain apparently ordered all hands to abandon ship, Bennett said, but he never heard that order. What he did hear was another sailer named Bill.

?Bill was crying and burning?at his gun, which was on fire, Bennett recalled. Seven crew members did not abandon ship, including one officer.

Three of the crew, along with the commander, worked on getting the fire out. Bennett worked on getting Bill out of the fire.

The ship should have sunk right there, Bennett said. It was about ready to capsize.

After dealing with the fire, the commander told Bennett to clean the ship.

?I said, ?If you want the ship clean, you clean it up,?? Bennett said. He said he couldn?t believe he said that to an officer, but ?he didn?t say a word.? After about five minutes, Bennett went to work cleaning up the ship.

?I was the one that had to pump that Japanese out of the bilges for about six weeks,? Bennett said. The pilot had been catapulted out of his plane onto the ship, everywhere. ?What was left, I kicked him over the side.?

?(The attack) stunned all of us,?Bennett said. One other crew member was killed in the crash.

?Bill died the next morning after we got him out of the gun,?Bennett said. ?And we buried him at sea. He was the one that saved our neck.

?I never was the same. Wilda said I changed a lot in that war, and I guess I did ? a lot of sleepless nights, and it doesn?t go away.?

?We were over there because we had to be there,?Bennett said. ?As far as I?m concerned, there are no heroes in a war. You do your job as best you can. We did our best, and that?s all you can.?

Sometimes, ?you think what?s it all for,?Bennett said. He thinks those in power should serve in the military and find out what war is.

Right after the incident, Bennett?s skipper tried to court martial three of the crew for not abandoning ship, Bennett said. Vice Admiral Kincaid came aboard and immediately removed the skipper from his position and dismissed the court martial. Bennett received a bronze star for his effort to save Bill.

?If he was hollering abandon ship, he was doing it with a mouthful of water,? Bennett said.

Bennett didn?t get to go home right away, he said. The ship, with a new skipper, Wahrenbach, was taken to dry dock and repaired and then sent across the Coral Sea, one of the roughest areas in the Pacific Ocean.

?We all got sick,? Bennett said. Of course, the new cook?s greasy pork chops didn?t help.

Bennett and the SC699 worked at Milne Bay, New Guinea, for two months guiding ships into the bay and transferring pilots to bring them in.

?I got to spend some time with the natives and did a little fishing,? Bennett said. He was sent home in January 1945 and discharged in the summer of 1946.

Upon returning to the States, he took 30 days leave and returned to Oklahoma to see Wilda. The two had known each other since the third grade, and Bennett?s whole focus was getting the job done so he could return to her.

His superiors were surprised that, while he was stationed at Brisbane, he never left the base.

?I didn?t come over here to find a girlfriend ? I came to fight a war,? Bennett said. His heart was in Oklahoma.

They married in June 1945, and Bennett took a job with Howard Hughes? company, which later became General Dynamics. He worked on a variety of projects, including the F-102, F-106, tracking systems, missiles and more. Later he worked for Marine Advisors and designed a device to measure current, speed and flows for the bathyscaphe that descended into the Marianas Trench in the 1950s.

The Bennetts moved to Sweet Home from San Luis Obispo, Calif., in 1973. They had a son, James, who had polio at 19 months of age. He grew up disabled and traveled to Sweet Home with his two sisters to attend college in Oregon. James died in 1993 from pneumonia.

The Bennetts? daughters are Linda K. Hervig of San Diego and Brenda Lou Kuchenbecker of Wasilla, Alaska.

In Sweet Home, Bennett went to work for G-2 Electric in Cascadia, then at Willamette Industries? Santiam Mill.

He was hurt in 1975 and took a medical retirement.

?Normally, I had pretty good duty,?Bennett said. ?The Navy treated me good. I learned a trade. I was happy, but I was anxious to get home.?

?I knew he would be home,? Wilda, now 79, said. ?I don?t think I ever considered the fact he might not come back. The Lord took care of him.?

?I don?t want people to think I think I?m a hero,?Bennett said. ?I did what I had to because of circumstances.?