Scott Swanson

Of The New Era

It was the end of the line Wednesday morning for the big Chinook salmon swimming in the holding pen at the South Santiam Hatchery.

He’d left the hatchery several years before, as an approximately 8-inch smolt, to seek his fortune in the Pacific Ocean. Now he was back, five times longer and 50 times heavier than when he’d left.

His instinct had told him to return and now he, and more than 200 others, were about to give their lives for the next generation.

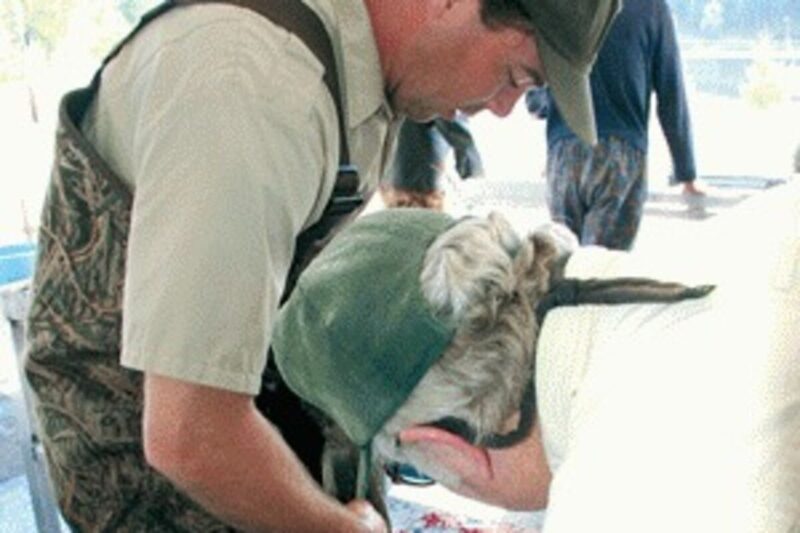

Volunteers grabbed the fish, which were swarming in the holding tank, and quickly killed each one with a couple of sharp blows from a small club to the back of the head. The fish were placed on a conveyor belt that carried them to a pavilion above, where more volunteers and some hatchery staff members quickly recorded identification information from tags in the fish, weighed and measured them, took samples to check for diseases, harvested eggs from females and sperm from the males, and finally, cut off the first few inches of the dead fishes’ noses.

“We cut the noses off so the fish won’t be counted by (Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife) surveyors,” who check the streams in the area for spawning wild fish, said volunteer Don Wenzel of Albany, a member of the Association of Northwest Steelheaders chapter.

Later in the day, after all the samples were taken and approximately half a million eggs were harvested to start the next generation of South Santiam Chinooks, Wenzel and ODFW biologist Karen Hans hauled a box of fresh salmon carcasses to Moose Creek, just east of Cascadia. They pitched the dead fish into the water at several locations along the creek.

Hans said the reason was to duplicate what happens when salmon spawn naturally – they die in the stream.

She said when the native salmon used to return in large numbers, before Foster Dam was built, they would spawn and die and their carcasses became “a very valuable nutrient input” to the ecology of the stream and the surrounding growth. The dead fish would provide food for animals such as bears and cougars, as well as smaller creatures, including insects and crawfish.

“Salmon are considered a keystone species on the environment here,” Hans said. “they make such an impact so that when they disappear, so many other species are affected by that.”

She noted that ODFW works with the state Department of Environmental Quality, which monitors stream conditions and generally prohibits dumping of dead carcasses in such waters. The salmon are deposited only after they are tested for disease and meet DEQ standards, she said.

Over the next few weeks more the process will be completed two or three more times until the hatchery has the 1.9 million eggs and semen it needs to artificially spawn nearly a million baby salmon that will be raised for release into the river. The sperm of one male is mixed with the eggs from one female, both of which have been tested for disease before the artificial spawning takes place.

The eggs are fertilized in 1-gallon buckets in the “hatch house,” where they are allowed to incubate for a month. Then staff members will “shock” them by shaking the buckets to reveal any weak eggs, which are discarded.

Hatchery Manager Brett Boyd said the eggs deemed worthy to continue are shipped to the Willamette Hatchery outside Oakridge, where they are raised to until they are about 2 inches long. They are shipped back to South Santiam Hatchery in April and November, depending on when they are scheduled for release as 6- to 8-inch smolts.

The harvested salmon will be deposited in other local streams, such as the Calapooia River and the mainstem South Santiam River near Trout Creek.

She said the depositing of carcasses in streams also helps the next generation of salmon, after they hatch, to survive.

“If the carcasses are not there and fish hatch out, they don’t have that food source and it makes it that much harder for them to survive,” she said.

“We try to do the best we can with what we have. We’re not going to be able to mimic the natural system. We’re trying hard to get this going until the fish start coming back large numbers.”