Scott Swanson

Of The New Era

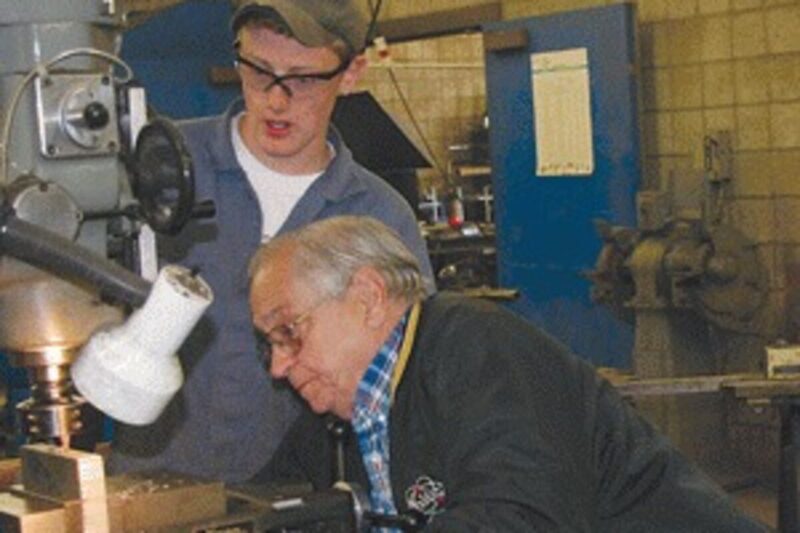

Four times a week in the springtime, Karl Giegl enters the metal shop at Sweet Home High School. A small, quiet man with a sense of humor, he’s dwarfed by some of the teens in the workshop.

But when he walks up to a young man working on a milling machine, his eyes sharpen and he’s all business as he watches the student working on a project. The teen listens when he murmurs words of advice, in a slight German accent, because he knows what he’s talking about.

Giegl (rhymes with “beagle”), 81, is a veteran machinist who learned the trade in Austria when he was the age of the youngsters he’s helping now.

Born Sept. 26, 1925 in Liesing, a suburb of Vienna, he grew up in a family of seven children in Breitenfurt, a small village in lower Austria. After eight years at public school, his father said it was time to go to work.

“I was a little guy,” Giegl said. “My dad said, ‘people have to eat, so you learn to be a cook. Go to a bakery and learn to bake bread.’ We went to a bakery, owned by a friend of my dad’s, and the guy said ‘I can’t use him. He’s too small. He can’t carry a 90-pound bag of flour.’

“We went to a butcher and he said I was too small. ‘He can’t carry the leg of a cow.'”

His search for a trade ended when he saw an ad in a newspaper for a machinist. He went to work for a company that made scales, ranging from “laboratory scales to railroad scales.”

In August 1943, when he was 17, he was called into the German Army, to fight in World War II. Since he had background in tool and die making, after basic training he was sent to learn to repair guns.

“That helped me a lot,” he said. “I wasn’t a fighting man.”

He worked on small tanks, jaeger panzer tanks, during the invasion of France in 1944. When the Germans retreated from France, after two weeks of fierce fighting in which all their tanks were destroyed, Giegl wound up in Levercusen, on the east side of the Rhine River in West Germany.

A friend’s parents had a farm in Westferlen, near Hanover, and he went there to work after the end of the war in Europe, on May 5, 1945. While there he met his first wife, Anneliese.

Soon he had a job for a bridge construction firm, where he worked until 1947, when he and Anneliese returned to Vienna.

Vienna at that time was occupied by four armies, the Russians, French, United States and English. He found a job in the area where he had grown up, which was occupied by the Russians.

“They put me to work on aluminum castings. I was supposed to work as a tool and die maker, so I quit,” Giegl said. “They told me the Russians would put me in jail if I quit. It was really dangerous at that time. But nothing happened.”

So he went to work for an uncle, at an auto parts manufacturing firm. He remembers helping to make a piston ring and inch and quarter thick and 3 feet in diameter, for a steam engine going to Russia.

“We had to heat treat them,” he said. “We used a torch and charcoal to get the right temperature. What a job.”

He worked at a succession of firms until May of 1957, when he decided to emigrate to Canada. His wife stayed in Germany with her parents.

“It was easier to find a job if I lived alone,” he said. Once in Canada, he went to the immigration office in Hamilton, Ontario, where he was told that since he couldn’t speak English, he would have to work on a farm.

“I said ‘No way,'” Giegl said.

He found a German Jew who had emigrated to Canada and who ran an electrical motor repair business, who gave him three leads on companies where he might be able to find work.

The second one paid off and he was hired for $3.25 an hour to make stamping dies for electric motor laminations.

“That was good money,” he said. “My heart jumped five miles high.”

Giegle went to night school for four years to learn English and tool and die design. He and his wife Anneliese divorced in 1958, but she, their two daughters and a stepdaughter arrived in Canada in 1964, where they settled down in Toronto.

He moved to California in 1966, working for Hughes Aircraft in Costa Mesa and Newport Beach until 1976. In 1967 he married a German woman he met in California, Margit, but when he decided to move to Oregon in 1976, she didn’t want to go and they separated and later divorced.

Giegl moved to Sweet Home and got a job at White’s Electronics as a tool and die maker. He retired in 1995. He married his wife June in 1980 after they met at the Seventh Day Adventist Church, of which he had become a member. He converted to Adventism in 1974 after going to some evangelistic meetings and hearing a German Jew who had converted to Adventism.

“I grew up Catholic, married a Lutheran, and now I’m a Seventh-Day Adventist,” he said.

He has a small machine shop, in which he’d like to build a rotary steam engine.

“I’m working on it,” he said. “I have some parts stamped out.”

Since his retirement, he’s helped in the high school machine shop, where students are required to build a C-clamp.

“That’s quite a job for them to do,” he said. It forces them to go through the whole process.”

Metal shop teacher Al Grove said Giegle is “a very, very talented tool and die maker.

“It’s a skill from the Old World,” Grove said. “He started at age 14 and he’s doing it at 81. There’s a lot I can learn from him.”

Giegl said he enjoys working with “the kids,” who are willing to learn.

“I tell them my life story in the beginning,” he said. “It makes it more interesting for the kids. I tell them if you have a trade, if you get hired, the boss can tell right away if you know what you are doing.

“I give them my experience, what I have, over the years.”

Grove said Giegl is patient but demanding.

“He’s very good with the kids,” he said. “He doesn’t do their projects for them. He also expects them to pay attention.”