Sean C. Morgan

Of The New Era

“Did you smell that?”

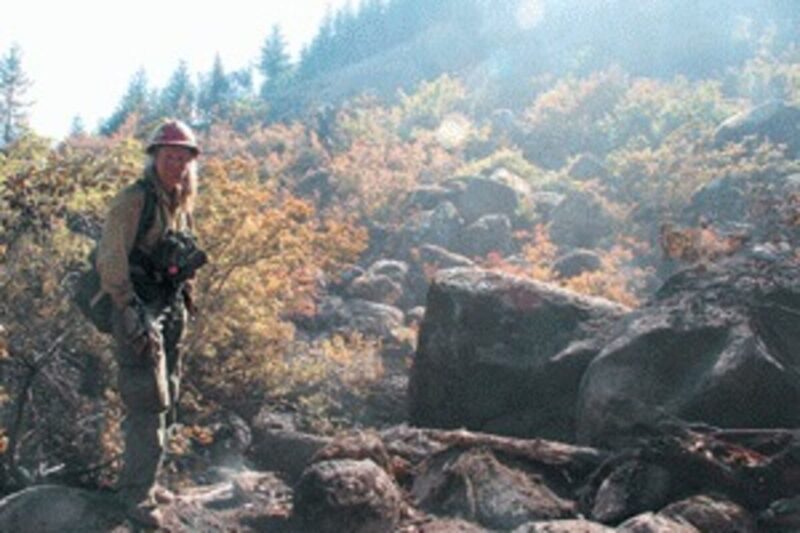

Karyn McNeil and her crew detected the scent of smoke as they picked apart a pile of debris and rotting logs on the Middle Fork Fire.

The top firefighting crew in the state, the Timberline Corporation, was among several that were busy mopping up a burnout on the 1,070-acre Middle Fork Fire last week.

The company is the top-ranked in a new system used by the Oregon Department of Forestry to ensure fire crews working in the state are the best possible.

“We’ve been in this business for over 20 years,” Timberline President McNeil said. “We kind of have this philosophy. We let our work talk for us.”

As the fourth-ranked fire in priority in Oregon and Washington, Middle Fork received a high priority for resources, Incident Commander James Walker said. That included the top two firefighting teams in the state, Timberline of Riddle and Grayback Forestry of Medford, both private contractors.

Nearly half of the resources working on the fire line are private resources.

Middle Fork, which burned a swath of timberlands near Green Peter Lake, 14 miles northeast of Sweet Home, had some of the top crews working on it, Walker said. Some are the equals of elite federal type one “hot shot” crews. They are called type two crews because they’re not a federal resource.

They are part of what’s called the “best value” system, which was phased in for the 2006 fire season, he said. These 20-person crews have participated in search for debris from the explosion of the space shuttle Columbia and in hurricane relief.

The idea was to get better quality among fire crews, Walker said, rewarding those with more equipment, better training and experience.

In 2002, the state used the closest and cheapest fire crews it could find, he said. A contractor could put together a fairly inexperienced crew and respond to fires.

The inexperience of some of these crews could be dangerous on the fire lines, ODF Spokesman Mike Barsotti said.

In 2002, ODF had more than 300 crews available to work, but the state could only afford up to 200 crews, Wilcox said. After instituting the best value system, the state ended up with only 158 crews going through the process.

Those were ranked, and Timberline was the top team.

Barsotti pointed out boulders the size of small cars just below Rocky Top in an area called the “boulder patch,” and McNeil pointed out one that was wedged against a couple of small trees, the only thing keeping it from tumbling downhill.

Her team was among many burning out the fire line. The burnout was a fire anchored to the fire line, ranging from a couple of feet to the width of two bulldozers. That fire is supposed to burn toward the forest fire from the line, removing fuels and creating an area where firefighters hope the main fire cannot cross.

Timberline burned out a part of the boulder patch and mopped it up. By the third day of mop-up, Sept. 11, Timberline had completed its objective in the boulder patch and moved downhill into a wooded area.

The boulder patch was tricky with logs wedged in among the boulders and rocks falling from above, Barsotti said. “It’s secure. We’re really pleased with it.”

The work is tough, but McNeil and her crew enjoy it.

“Ninety percent is mop-up, going in and digging up all the hot stuff,” she said. The mop-up can use water, or firefighters break apart the hot fuels, cooling the fuels.

“It’s enjoyable,” she said. “You feel a sense of accomplishment when you start one project and see what you accomplish. It’s a good feeling.”

Fighting a wildland fire brings a big adrenaline rush in the beginning, Barsotti said, but the later, longer mop-up requires discipline. That’s what Timberline and other top crews have.

“The real test is the mop-up,” McNeil said. When her guys are training she warns them the work is mostly digging, and it’s monotonous.

As a crew, a fire means only one or two days of running a hot fire line, where firefighters attempt to surround a fire and develop a secure line. Then they’re busy removing vegetation and fuels prior to the arrival of the fire.

“Timberline is very old-school, one foot in the black and one foot in the green,” McNeil said. Her team tries to stay as close as possible to the perimeter of a fire.

Crew members Charles Urbank of Canyonville, who’s been a firefighter for two years, Matthew Spencer of Glendale (five years) Eugene Hopkins of Canyonville and Brad Yeats (16 years), were working on a pile of debris Sept. 11, the day before many crews, including Timberline, were demobilized. They were working downhill from the boulder patch following another crew along the fire line.

“We’re on a mission, searching out the hot spots that get buried,” Yeats said.

In a gloved hand, Spencer held up a decayed lump of wet wood, steaming in the afternoon sun. He broke the loose wood apart, explaining that the heat will dissipate into the air.

“I’m scared to death of fire, but I’ve got an understanding about it,” he said. “It takes experience, and this type of work is not to be taken lightly.”

“It’s camaraderie,” Spencer said of heading onto fire lines year after year. “I can’t imagine not being out here.”

Part of what makes their crew special is the level of training, Hopkins said. Even beginning firefighters need to know how to program a radio.

When ODF says, “we want performance, performance, performance, it’s hard to argue with that,” McNeil said. The best value contract is a work in progress. It can be improved, but all contracts are works in progress.

Best value means ODF will get a quality product, she said. She credits ODF management for developing the system. “It’s those guys in there right now that have made it better for these guys out here.”