Dr. Alan Blake was one of Dr. Gary Goby’s customers – at Goby’s lumberyard, Goby’s Walnut Products, located in Aurora.

Both medical doctors practising in Lebanon, they had varied interests, and both were interested in fine woodworking with quality hardwoods. Goby had built a side business harvesting old, oversized, often dead and dying maple and walnut trees, which he processed into slabs for use in woodworking projects.

That’s one of the many things Blake did when he wasn’t delivering babies and practicing family medicine in Sweet Home and Lebanon.

On Aug. 25 Samaritan Sweet Home Medical Center staffers gathered with Goby and family members to dedicate a memorial to Blake, who died two years ago after suffering a series of strokes.

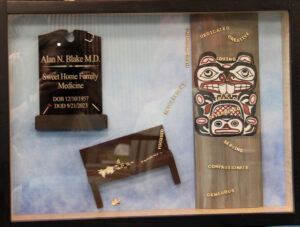

To honor Blake’s memory, the Sweet Home Center staff asked Goby, who is now retired as well, to create a custom shadow box that reflected Blake’s medical career and his passion for woodworking.

Blake’s widow, Zsuzsa (pronounced “Zu-sha”) and her sister Yoli Pinter, reflected on his “Renaissance man” personality and interests in their living room shortly after the memorial.

Active From the Start

Alan Blake was born Dec.10, 1957 in Carrollton, Ky. His family moved around “a lot,” Zsuzsa said because Alan’s father was a construction engineer.

When Alan was in sixth grade, the family moved to Seattle.

File Photo

He met Zsuzsa (pronounced “Zu-sha”) at the University of Washington, where he was working toward an undergraduate degree in physics; they married in the summer of 1979, after he graduated.

But things didn’t work out quite the way Zsuzsa had planned.

“He came over one day and said, ‘I’ve changed my mind. I’m not going to pursue physics. I’m going into medical school.’

“I said ‘Wait, wait, what?’”

Alan’s grandfather had been a physician, but his parents had wanted him to be an engineer, she said.

However, Alan had gotten into a conversation with a friend who was heading to medical schools, whose father was a doctor, and they’d gotten to talking about rural medicine.

“And Alan said, ‘Light bulb! What am I doing in this physics thing?’ So that was all she wrote.

He went back to school for a year of pre-med, then was accepted into the University of Washington School of Medicine.

“I had no idea what I was getting into and actually, he didn’t either,” Zsuzsa said. They found out when he began his residency in Boise, Idaho, where he had chosen to go because he could get specific training there, she said.

“You have no idea how grueling a residency can be,” she noted.

Alan had toyed with the idea of going into surgery, but he decided that was “too confining,” Zsuzsa said.

“Back then, family docs still were doing everything, essentially, and that’s what he wanted.”

Surgery was “too confining.”

“‘I want to deliver babies’, so that’s what he did, and it was extremely demanding,” she said.

But, she added, “he was really thriving. It was a perfect fit for him.”

Settling in Sweet Home

When he finished the residency in Boise, they looked around for a place to settle down. That turned out to be Sweet Home. They arrived in 1988 and Alan set up practice with Dr. Bruce Matthews in what, Zsuzsa says, “was technically a six-person practice.”

The doctors worked out of the old Langmack Hospital building, at the corner of Highways 228 and 20, which then was owned by Sweet Home Fire.

They provided a wide range of medical care in Sweet Home, including serving as medical examiners when need be, she said. “I’m not even sure I can remember everything they did.”

Meanwhile, they raised four boys: Nathanael, Nicholas, Isaiah and Zachary, who has Down’s syndrome.

woodworking prowess. Photo by Scott Swanson

Dr. Blake was involved in much more than just his practice and parenting during those years, though his efforts were often combined, she said.

“He wasn’t involved in the community, per se, as, you know, councils or things like that. But he was extremely involved. He still did house calls and things.”

He and Zsuzsa led small groups at their church and he served on the board.

and Allan went on medical missions, taking trips to Bolivia, Honduras, Mexico, often taking his wife or older boys along.

“He was always interested in missions,” Zsuzsa said.

In 2007 they spent a year in Hungary, Zsuzsa’s birthplace, where he became conversant in Hungarian – “an extremely difficult language,” his wife said. “He pretty much mastered that.

He had learned Spanish because he was doing medical stuff down there.

“Alan was a man of many talents. He was a Renaissance man.”

He also was an artist and master woodworker, who produced Northwest Coast Indian art that helped pay their way through medical school – “paintings, silver bracelets, a couple of gold bracelets, because we were in Seattle, that worked out perfectly. There was a demand for them.”

“That was a huge part of his life when we first met,” she said. “He had gone up to Alaska when he was 15, where he learned how to do wood carving in an Indian tribe. Then he expanded into silver work.”

It wasn’t big bucks, she said, “but we survived.”

He enjoyed reading widely, gardening, and photography – at all of which he was very proficient.

He also volunteered at the Pregnancy Alternatives Center in Lebanon, now Obria.

“He worked down there with Debbie Tracy (the center’s founder) and did the ultrasounds,” Zsuzsa recalled. “He was really into that.”

Woodworking, though, was his other real passion.

Alan did a lot of the remodeling in the house they bought in Sweet Home and he created most of the furniture in the dining and living room that isn’t upholstered.

“He would joke, ‘Yeah, I’m just going to quit medicine and be a woodworker,” Zsuzsa recalled, adding, and pointing to the finely crafted dining room set her husband had created in the federal style he preferred: “and he could have. The quality of those chairs, it’s like, ‘Wow.’”

“He was one of those guys that, whatever he set his mind to exactly to do, he could do it,” Pinter said, adding, “It was very frustrating for us,” as she and Zsuzsa chuckled.

“He was really good at pretty much everything he tried,” Zsuzsa said.

Like treating patients and, particularly, delivering babies.

Pinter noted that he had delivered more than 1,700 infants during his career, first in private practice and then at Samaritan.

“I think what made him a reliable doctor was that he knew his limits,” Zsuzsa said. “They were wide and broad, but he knew when he needed to refer and he didn’t get into trouble because, it’s like, ‘OK, this is past me.’”

She and Pinter said they have heard from many people who have told them stories of how Dr. Blake “had affected their lives and the good that he had done for families, people, individuals.”

Blake and Matthews continued “for years, and then this thing started changing,” Zsuzsa said. Administrative burdens were mounting and that’s when they connected with Samaritan.

“Everybody got bought out everywhere, because it just was too hard for a rural physician, very overwhelmed with, just, busyness.”

That was in 1992.

New Challenges

In 2015, while on a medical missions trip to Ukraine, Alan suffered a severe stroke, which paralyzed the right side of his body, rendering him unable to speak or walk – or even swallow, initially.

Alan worked vigorously to recover, regaining his abilities because he wanted to return to medicine.

“He was always after us to do therapy, whether it was speech or physical therapy, or occupational therapy, Zsuzsa said. “He was just maniacal.”

File Photo

Along the way, he visited a therapist at Samaritan Lebanon Community Hospital who was helping him relearn those basic skills, chauffeured by his son Isaiah.

“That is one of the beautiful parts of that story,” Zsuzsa said, relating how, while taking his dad to appointments, Isaiah met a young woman who was interning with Samaritan as a speech therapist and … one thing led to another and now she is Alexa Blake.

In 2022, Alan took the medical boards exam and passed it.

He went skiing. He wanted to regain his driver’s license.

“Fortunately, I won that one,” Zsuzsa said, laughing.

Then, in September 2023, he suffered another stroke.

“He’d just been improving so much, and you know, there’s always risk for another stroke once you’ve had a stroke,” Zsuzsa said. “Well, really, in my mind, I just didn’t think about that very much because he had been improving so well.”

Although the second stroke initially seemed less severe, after a few days Alan began to decline and the end came quickly, in an ICU in Portland, on Sept. 31, 2023. He was 65.

“It was our 44th anniversary.”

Memorial Reflections

Goby said Alan Blake would come to him for wood for his projects and after his death, Blake’s family and the Samaritan Lebanon Hospital Foundation contacted him about creating a memorial.

The memorial was originally intended for the garden area outside the clinic, but Goby said that they decided to move it indoors, into the lobby.

“I drew up a plan for the shadow box and ran that by them and I talked with employees about some of the qualities they recognized in him,” Goby said.

“He was skilled with his medicine and skilled with his hands. Those are not qualities you always find together.”

He said he decided to create the shadow box of fiddleback maple and ebony.

“Ebony’s very rare,” Goby said. “I wanted to use something rare, beautiful.”

The box contains a small tombstone with a stethoscope and some other medical instruments carved into it.

The box contains a small tombstone with a stethoscope and some other medical instruments carved into it.

He also added a workbench “to have a place for him to hang his stethoscope up and come home and not worry about his patients.”

Goby said he was able to find some small laser-cut letters that he arranged on the work table “as if he were designing names” and which Goby used to represent some of Blake’s qualities and “life skills”: “Patient,” “Compassionate,” “Intelligent,” “Creative,” “Serving” and more.

“He was interested in Alaskan totem pole art so I included a beaver carving on there that represented his industry as a busy, active life,” Goby said, noting after a brief pause for reflection: His personality and mine are somewhat similar.”

Brandy O’Bannon, executive director of the Lebanon Community Hospital Foundation, said the memorial was a “staff-led project.”

“Medical Director Dr. Juliette Asuncion and her team at the Sweet Home Medical Center really wanted to pay tribute to their long-time mentor, colleague and friend,” she said.

“We were glad to connect the team with Dr. Gary Goby, who designed and crafted the memorial, with consultation from the Blake family. We are grateful for donations, which made this project possible, and hope that patients and friends of Dr. Blake will find the memorial meaningful and honoring of a great legacy.”