Sean C. Morgan

There’ll be no more excuses.

“You graduate as a teacher, and you get a bachelor of science,” said Sweet Home High School Assistant Principal Keith Winslow. “Are we treating this (education) as a science? No.”

Students fail. Students drop out. Educators come up with a variety of reasons why, such as the poor home life some students have.

In SHHS’s new Professional Learning Communities program, statements like that aren’t acceptable, Winslow said. Instead, the teachers and administrators will look at data scientifically and start learning what they need to do to put the learning into education.

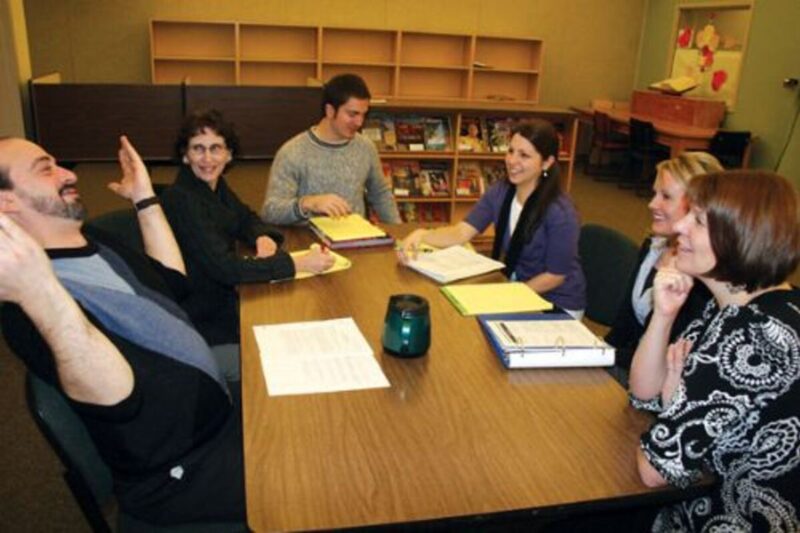

“We’re finding the time to get together in the PLCs to look at data to inform our teaching – to direct our teaching,” Winslow said. The small groups, based largely on departments, start the week meeting on Mondays from 7:30 to 8:20 a.m. at the school.

It’s a chance for departments to get together, said Eileen McHill, a language arts teacher. They have meetings to run the department, but they haven’t had the chance to compare notes and improve the teaching.

This year’s juniors must pass the state reading test to graduate, said Pam LaFollette, a language arts teacher, and her department sees this process as an important piece to helping students meet that requirement.

“This is not another bandwagon kind of idea,” Winslow said. “It’s not another program. It’s a process that’s going to take three, five, seven years – an ongoing process.

“We’re looking at a variety of things,” said Jim Costa, a language arts teacher. “We’re looking at student success on different levels.”

The groups are attempting to answer four questions about learning, starting with what data they have from last year.

The first question is, “What do we want kids to learn?”

“Our state standards are a mile wide,” Winslow said. “What essential skills in your content area do kids have to know – the most important things in your content area?”

The second question is, “How do we know they learned it?”

The question and answer involves a cultural shift, Winslow said. “It’s a cultural shift from, ‘I taught it; you should have gotten it.”

By the time the students take their state assessments, they’ve either got the information and skills they need or they don’t, he said. Educators need to know before that, so they’re forming smaller assessments throughout the trimester to see if kids are learning.

If students in a particular class are missing a particular standard during the trimester, teachers can figure out what they did, conferring with their colleagues who did well in a particular standard about their methods.

The third question is, “What are we going to do if they don’t get it?”

“This staff is committed,” Winslow said. “We are not going to use the excuses we have in the past.

“Here’s what we know: There has not been a kid in the two years I have been here that hasn’t told me I wish there was a way – there’s not been a kid that’s said screw this, not one – not really.”

Even the hardest of students would look at educators like they’re dumb if they asked the student whether they would value it if they were juniors on track to graduate, Winslow said. Students all would value that chance, and the goal is to figure out how to help them get there.

The answer is more time and support within the school day, Winslow said. The first steps are already in place with a new study hall during the lunch period. All freshmen must use the period, and anyone receiving a D or an F in any class must attend.

The study hall is an opportunity for students to receive extra help one-on-one or in groups, Winslow said. It is not a punishment, and students who are making the Cs or better receive a longer lunch period, a privilege.

“There’s a ton of interventions we can do,” Winslow said. “We’re going to get into some huge discussions, heated discussions, down the line.”

Among those discussions will probably be a question: “How long do you give a kid to make up or retake a test?”

Winslow asked, What if academic grades can be separated from behavior issues, like deadlines?

A student who knows the material and can pass the tests but turns in work late might receive good academic grades while being held accountable for the behavior, perhaps earning a low grade in behavior.

Discussions like this will be part of the process, Winslow said.

The fourth question is, “What are we doing with the kids that do get it?”

The high school staff is just starting and have not gotten to this question yet, Winslow said. “We’ve got all sorts of ideas. We need to be able to enrich these kids without that meaning more homework.”

Overall, the professional learning communities are meant to be a process to help kids learn, he said, and already it’s finding success.

With the study hall, Winslow said, he is hearing students say that 25 minutes isn’t enough time.

“It (the PLC process) may get to the point we need to change things in school, structurally,” Winslow said. “We don’t know what that is right now.”

Data are coming in now, he said. The staff is committed to examining and using it, and the staff members are still asking questions.

“We have more questions now than we have answers. We’ve seen some data already that is showing that this is working.”

The focus is shifting from “teaching” to “learning,” he said. Though he is a 31-year teaching veteran, “I probably have never been as energized.

“Kids want to do well. They want to learn,” Winslow said. “They want to be successful.”

The teachers want to help them do better on their state tests, Costa said.

Sometimes they have a disconnect between that desire and their minds, Winslow said. “What we are doing is giving more time and support so they can do the work at a passing standard.”

“I think because we’ve been focused on it so much, they (the students) are becoming more serious when they take the test,” Costa said.

This is going on in other schools, and they’re finding success across the nation, with higher graduation rates and attendance and fewer students flunking out and dropping out, Winslow said.

He hopes that by studying the information they collect through the program the high school could someday get rid of its essentials classes, where students repeat failed classes.

If students can get the time and support they need to pass a class in the first place, they won’t need to retake them, he said.

It’s local research into local education, more science than art, Winslow said.