Roberta McKern

“Halt.”

The order came from the darkness as a lone figure traveled down a moonlit Sweet Home street.

Instead of stopping, the figure turned. Shots from his gun rang out in the silence. More came from the town’s lawman, who had set up a roadblock to catch a thief. A running gunfight ensued, the sounds of which awakened the sleeping town.

Thus starts Scenario No. 1.

Meanwhile, miles away – and reflecting events from an earlier era – a tombstone in a cemetery near Skagway, Alaska, reads: “Frank F. Reid, Died July 20, 1898. He gave his life for the honor of Skagway.”

And how did Frank H. Reid deserve to be so honored? He died in a gun battle that killed Soapy Smith, the crime CEO of that city.

However, Reid boasted a more local history, as a teacher in both Cascadia and Sweet Home. In the latter town he shot and killed storekeeper James Simons.

Scenario No. 2 then follows his saga.

These stories appear in Roy Elliott’s “Profiles of Progress,” published in 1971, and Margaret Standish Carey and Patricia Hoy Hainline’s “Sweet Home in the Oregon Cascades,” published some eight years later. Elliott takes both scenarios into account, but the ladies were concerned with Reid’s local misadventures. Googling “Soapy Smith” and “Frank Reid” offers some help, too.

Though the Skagway events come first chronologically, we’ll start with the Sweet Home shootout, because no one was killed or even injured and the mysterious stranger escaped.

It started with cord wood and an unusual river drive. Downstream, the Lebanon paper mill had in 1906 switched from using straw to wood pulp to make paper for boxes and bags. So the wood of choice became white fir, initially easily harvested in the vicinity. This provided Sweet Home residents with employment and became a community affair with a big picnic at the end of a drive.

White fir logs were sawed into the desired lengths, then split and stacked in tiers to dry near the Pleasant Valley Road where High Banks stood above the river. A massive pile accumulated ahead of the day the mill representative decided conditions were right to float it down to the paper mill. Thousands of cords went into the water, blanketing the river’s surface.

How the drive was managed, of course, is not clear. Perhaps by men working with peaveys and pikes along the river’s edges aided by horses pulling wagons into the water. We have trouble imagining young men like Elliott hopping from chunk to chunk of white fir in calk boots.

At any rate, the demand for the cord wood proved greater than the local people could satisfy, so a crew of 40 Italian woodcutters was hired. These were the robbery’s victims. Only one of the men was proficient in English. He spoke for the others and handled their arrangements, which included having their camp upstream at Big Bottom.

One day, while the woodcutters were at work decimating the white-fir stands in a way Elliott later regretted, an unusually large payroll was delivered to the cook, who looked after it until the English-speaking foreman and others returned to camp, as was their custom. But the payroll didn’t reach the foreman. Instead, it was taken from the camp by an armed robber, who paused long enough to search some of the men’s belongings for money.

At the time, Sweet Home had official or unofficial lawmen in the Keeney twins, George and Jerry. Photographs show that it was difficult to tell them apart. They worked well together and had once served the area as game wardens. That job had little appeal, however, because a warden was rated depending on the number of arrests he made. Anyone working toward a higher rating gained unpopularity in an area where farmers ate roasted venison to save their pork and beef animals for market. At least one warden had his saddle horn shot off while riding horseback.

In their roles as local lawmen, the Keeneys had set up the roadblock to halt the unknown armed man walking through town in the moonlight. The ruckus in the street was the event’s most exciting part, because no one was ever apprehended for the robbery. Suspicion fell upon the cook and the foreman. Was it an inside job?

So, now, let us leave the first shootout for the second, although we’re not yet through with the woodcutters.

Wikipedia lists Reid as a Linn County schoolteacher, a soldier, an engineer who surveyed Skagway, and as a bartender working for Soapy Smith. We learn of his local past in “Sweet Home in the Oregon Cascades.”

The first school he taught at here was in Cascadia. By then he’d already served as a lieutenant with a company of Oregon volunteers and had studied engineering. He had some education, an important consideration, for he turned out to be an agnostic by philosophy who professed his beliefs, one being that all we can perceive comes from human experience (at least, according to a dictionary).

This perspective shocked Cascadia parents, whose views remained more traditional at a time of great leaps forward in science, when such “ologies” as geology, paleontology, biology, anthropology and archaeology were making great strides as education became available to more people, thanks to rising technologies.

In 1859, Charles Darwin’s “The Origin of the Species by Natural Selection” came out after he had spent considerable time studying how finches had changed to fill different ecological niches in the remote Galapagos Islands. He was just one of many putting forth ideas of evolution.

Along came such slogans as “survival of the fittest” and derogatory phrases like “Well, I’ll be a monkey’s uncle,” regarding the possibility of change among humans by a line of descent. (Really, the monkey was more likely the uncle if that explains much about human activity.)

As it was, plant and animal breeders who used selective selection should have felt close to home with the idea. At the same time, huge petrified bones were being discovered in various parts of the world, including the American Middle West and Oregon’s John Day country. Paleontologists vied to assemble them into skeletons of long-dead creatures. Sometimes they argued over which skull went with what body. With ponderous steps, science illustrated that the earth was old, older than hitherto imagined, and, for those who preferred traditional beliefs, unimaginable.

If Frank Reid harkened to such knowledge and included it among the standard subjects of writing, reading, arithmetic and geography, it very well could have set local teeth on edge. Whether because of his science or philosophy, people abhorred Frank Reid. Cascadia’s population likely didn’t support many numbers of schoolchildren, but their parents boycotted him. His landlord kicked him out, too. As an ex-Army man, Reid knew how to tent out, which he did right beside the school, waiting for either pupils or a paycheck. Neither showed up.

Leaving Cascadia behind, he resorted to traveling to Sweet Home, where he resumed teaching.

And he killed a man.

Perhaps as Hoy and Hainline speculated, Reid’s reputation followed him. At any rate, he met with the disapproval of James Simons, a local merchant. It’s claimed that Reid was interested in Simons’ niece.

One day the men encountered each other at about 22nd Avenue and Long Street before the construction of the church.

Reid had been hunting with a friend, so he was carrying a gun. Simons had an armload of wood for his store. They exchanged disagreeable words, and Simons hit – or threatened to hit – Reid with a chunk of wood. Reid responded with gunfire.

A trial ensued, and Reid was acquitted. The moral is: Do not threaten a man with a loaded gun by whacking him with a piece of firewood.

Had it not been for the Skagway shootout, Reid’s story would have ended there, although a tree with a cross carved into it stood for years near where the event took place. However, when the church was built, the tree came down.

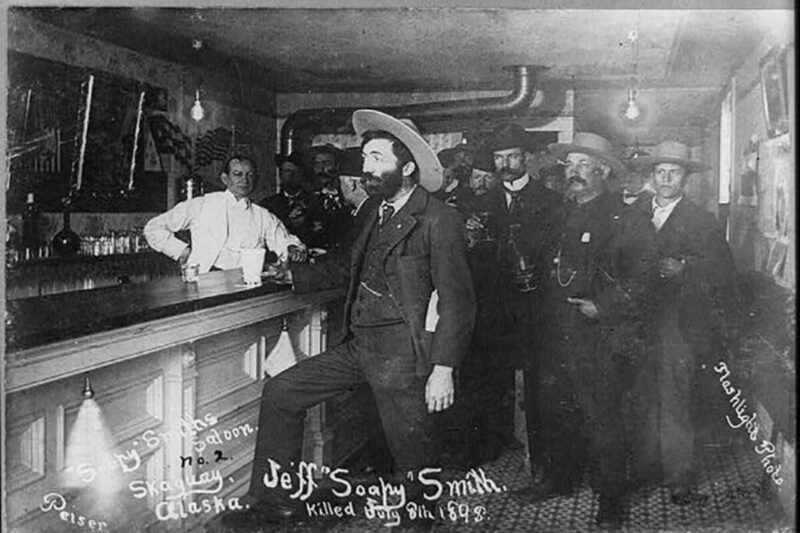

So let’s take a look at how Reid himself was put down in 1898. First, we’ll consider Jefferson Randolph Smith II, who became better known at “Soapy” from a scam in his younger years involving soap allegedly containing prizes within their wrappers. Sure, there were winners sometimes; however, they usually turned out to be Soapy’s friends.

But Soapy had the makings of a CEO, organizing dishonest pursuits in such Colorado cities as Denver and Creed before arriving in Skagway. Reid was then working as one of Soapy’s bartenders at the local Klondike Saloon, so he had a good view of these nefarious affairs.

At any rate, a miner came to town with $2,700 in gold. He got into a game of three-card Monte with three of Soapy’s men, lost everything, cried foul and did not want to pay up. The winners snatched the gold and ran. When questions arose, Soapy declared it to have been a fair card game.

Men in Skagway had their doubts. A group calling itself the 101 arranged a committee meeting on the Juneau wharf. They were at one end, and four armed guards, including Reid, were at the other.

Soapy arrived with a Winchester to see what was happening. Gunplay ensued. Soapy’s last words were said to be, “Don’t shoot.” Frank Reid, too, was shot in the shoulder and groin area.

He lingered for 12 days and died a hellish death. Soapy, like any criminal, was buried outside the churchyard.

Reid likely made it inside the cemetery gates under the epitaph “Died for the Honor of Skagway.”

Considering that these tales are more than a century old, we must explore a few doubts. What of the Italian work crew? Were the robbery an inside job, surely one of the 38 men would have noticed. The cook and foreman aren’t counted because they were suspects.

Or were they? The dark figure walking down the middle of a moonlit Main Street was not identifiable as Italian or otherwise.

It is wrong, too, to figure that the members of the work crew had no awareness or sagacity among them. Someone likely noticed if the thief was present, unless the cook and foreman were in cahoots with an outside party.

According to Elliott, the locals called the Italians “dagos,” making them seem more like outsiders.

Did they keep to themselves? Did everyone else prefer it that way? Blaming the crime on foreigners had two advantages: It solved the matter — sort of – and meant that no one here need be suspected.

Frank Reid, too, was an outsider, but his crimes seemed obvious. He shot James Simons, however, in what Roy Elliott called a tragic accident. Did he shoot Soapy Smith in some kind of similar impulse to defend himself? Maybe, but it’s alleged that the fatal shot had actually been fired by someone else.

There’s plenty of doubt, of course, when considering any crime of the distant past. A few lines describe the incident and speculation fleshes out petrified bones which may or may not have the proper head attached.

Even if two wrongs don’t make a right, they can perk up an interest in local history. As it is, there are more facets to that history than we tend to consider.

Sometimes we think people in the East Linn area lived in some kind of secluded shelter devoid of news from the outside world, but then we forget the toll road over the Santiam Pass to other parts of the Willamette Valley. Connections existed to allow the outside in.

As the stories about the Italian woodcutters and Frank Reid show, we were far less isolated than we think.