By Roberta McKern

For The New Era

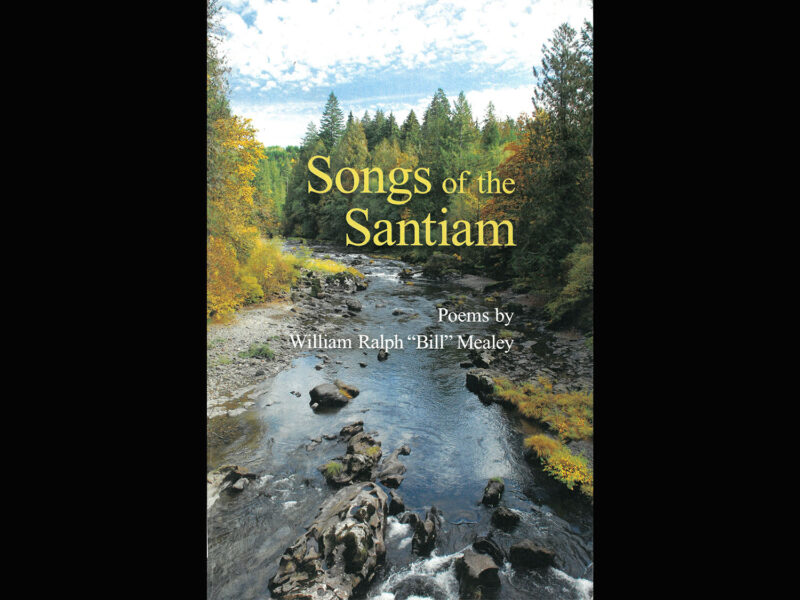

At the East Linn Museum, we have been browsing through a book of poetry entitled, “Songs of the Santiam,” written by William Ralph Mealey, a well-known resident of the Foster area before the Santiam’s song was altered by the building of the Foster dam reservoir.

Bill composed rhyming verses throughout much of his life, although he was best known as a lumberman and a farmer. Writing poetry was an intellectual pursuit, one in which he could be in touch with his memories of the past and especially with his love of the Santiam River and its natural charms.

Born in 1870, Bill died in 1948, but fortunately for us, his grandson compiled his poems into “Songs of the Santiam.”

For many years, Bill and his brother, Orange Judd Mealey, operated a sawmill east of Foster. Their parents had earlier run a roadhouse for travelers going along the river to and from the Santiam Pass on the toll road, so Bill knew the river from a young age particularly from hunting and fishing along it.

There had even been a post office with the Mealey mark with Judd as postmaster.

(Post offices were fairly easy to get in the late 1800s if an area had a seemingly growing population.) When Bill and Judd took off for the Alaskan gold fields, the post office closed, ending the “Mealey” post mark in 1898.

Although Judd was close to Bill and had been in Alaska with him, in Bill’s poems about the Copper River, Judd is not mentioned. The poems are autobiographical, for the most part. We speculate that Bill had a reluctance to include those he knew, perhaps feeling it would be an invasion of their privacy.

The Alaska trip fueled some of Bill’s poetry. Before their return to Oregon, they had dragged a sled about 1,000 miles and Bill was inspired by their experiences along the Copper River, including survival through a terrible storm with only a flimsy tent and warm blankets to prevent death from the wind and intense cold. Several poems feature the Copper River.

The gold of Alaska did not glitter for Bill and Judd.

The waters of Bill’s favorite Oregon river offered a different opportunity, and the two constructed a sawmill on the Santiam east of Foster. Though the numerous rumors claimed that Bill and Judd had come back with pockets full of gold, Bill said not so.

But it stimulated his creative mind.

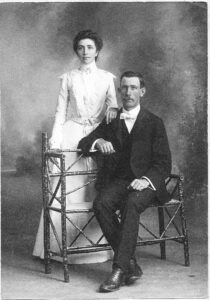

One poignant and very personal poem does appear in the book. Written after the death of his wife, Fanny Hamilton Mealey, following the birth of their sixth child, Bill departed from his usual aloofness to envision her beautiful blue eyes.

Their memory haunted him. She had been his great love. He did not remarry.

Nearly 100 years later, the late Rachel Fanny Vogel visited the museum and the Mealey family history there. Large photographs of Bill and Fanny hang among pictures of early East Linn settlers arranged around the main room. (She also volunteered in the research room and she said her father would work all day and come home and sit at his typewriter composing his poems.)

For Bill, writing poetry had much to do with the heart’s longings. Returning to the renewing quality of nature formed one of his main themes.

In 1924, the mill burned. Sometime later, it featured in one of Bill’s poems entitled, “The Fir Has Claimed Its Own.” The mill’s remains had been overgrown by a fir tree and the site was going back to nature.

Bill might stress the importance of hard and steady work, but his verses often stressed his longing to be on the river fishing, or hunting. In various poems, trout ranked high, although deer, grouse, and or a young bear, fed on huckleberries, could appear on the menu.

There was practicality regarding Bill’s views on the wild.

His poems also lean strongly towards farming. Indicating that he had a sense of humor, he invented an alter ego, a Scotch-Irish farmer of a respectable age named William Andrew McQuirk.

“Uncle Billy,” as he became called, had a Calvinistic view of hard work – it’s good for you – and, like Bill, a longing to visit a trout pool for a good mess of fat fish which would fry just right. Through Uncle Billy, Bill could regret the modern age which included tractors, cars, and motion picture shows. Uncle Billy believed in plowing with a steady, plodding horse. He wasn’t overly fond of the automotive age and he found the actions of actresses and actors on the silver screen deplorable.

Bill had Uncle Billy McQuirk talk in the vernacular. The vernacular was meant to reproduce the speech of poorly educated people. Most of us had teachers who discouraged us from using words such as ain’t, git, jist, and I’m agoin. It was often used to poke fun at what was rural versus the urban.

It was a very popular way of writing poems in the late 1800s and early 1900s and writers looking for realistic accuracy considering dialects, could drop so many g’s, make so many contractions, and create so many strange spellings as to become undecipherable But William Andrew McQuirk missed that fate. Even if he is sometimes critical of life, he knew the value of bacon and eggs and a good night’s sleep, not to mention a successful day of fishing resulting in a mess of those fat trout.

John P. Russell edited and then owned The New Era for part of the time Bill was writing verse, and he and Bill were good friends. (The museum has their matching typewriters sitting side by side below the pictures of Bill and Fanny. “Standards” have an innovative circular arrangement of the keys where the typefaces strike paper. The “Standards” are remarkable for not being very standard.)

John Russell also did sketches for The New Era using the vernacular, although when he produced one for the paper about Bill, he did not do so.

It seems likely Russell encouraged Bill’s poetic production. Many of Bill’s poems could be used to mark holidays in The New Era. These include tributes to George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, as well as ones to the honored dead, those soldiers killed in our nation’s various wars.

One such poem includes men dressed in uniforms of grey, blue, and khaki representing Confederates from the American Civil War, along with the Yanks from the Grand Old Army of the Republic, and those boys in khaki representing World War I and perhaps World War II depending on when the poem was written.

When Bill died in 1948, the latter war was still ending, considering the occupations of Japan and Germany.

It strikes us that Bill’s friendship with Russell may have led to his becoming known as the “Poet of the Santiam.”

He also wrote about Sweet Home, mainly a lament regarding the proposed damming of his favorite river. In the 1940s such a proposal was made with the dam situated north of the town at the Narrows. All Sweet Home and up the valley would be drowned; Bill and the town were against it.

Bill wrote of having a cabin up a hill where he could escape to tranquility. In poems, the usual mess of trout featured as a satisfying meal. For his bed, hemlock boughs sufficed with his folded jacket for a pillow. There he might remember instances about which he wrote such as the trips seeking gold in Alaska’s Copper River.

Many years after his 1898 experiences, he wrote of visiting abandoned diggings on Quartzville Creek when his knowledge of earlier times let him see where gold seekers had moved rocks and gravel around and he’d found a worn-out sluice box discarded in the bushes.

The poem was one of several in which he realized time does not go backwards.

Many times, in the Poet of the Santiam’s verses, solitude stirred the secret longings of the human heart.

At the East Linn Museum, we are grateful to have a copy of Bill Mealey’s “Songs of the Santiam.” Like many of his poems, artifacts in the museum and collections inspire us to look back and wish we could actually return to the past. But even if we can’t go back, we can remember through Bill’s poems and perhaps be inspired to look into our own histories while putting together a verse or two. We can appreciate and be inspired by the Poet of the Santiam.

The museum will be closed for the months of December and January, opening again in February.

So, we wish you happy holidays!