By Paul F. Petrick

The Aug. 15 Trump-Putin summit in Anchorage would have been perfect for Will Rogers.

The cowboy comedian got miles of material out of the post-World War I peace and disarmament conferences during his heyday, which tragically ended along with his life in an Alaskan plane crash exactly 90 years before the Trump-Putin powwow.

Like today’s conferees, Rogers and aviation pioneer Wiley Post were in Alaska seeking ways to bring the United States and Russia closer together.

Well, at least Post was. He was exploring possible mail and passenger airplane routes between Alaska and Siberia. Rogers tagged along to chronicle their adventures in his daily newspaper column.

That column was read by 40 million Americans in 400 newspapers. It was just one of many mass media frontiers that Rogers conquered during his truncated life.

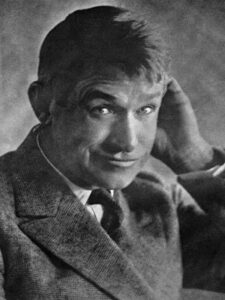

Born in 1879 in what is now Oklahoma, but was then known as Indian Territory, Rogers mastered the lariat at a young age on his father’s ranch. Five-sixteenths Cherokee, his first profession was cowboy in the waning days of the great cattle drives across the Great Plains. With the frontier yielding to civilization, Rogers graduated from cowboy to cowboy-entertainer, cashing in on the nostalgia for the Old West in rodeos and Wild West Shows.

Success soon brought him to the vaudeville circuit, where his sardonic wit enabled him to spin humorous yarns while he twirled a rope.

His voice quickly eclipsed his wrist as the most integral part of his act and soon more people flocked to his performances for his comedic stylings than for his rope tricks. Rogers would even go so far as to mess up a rope trick on purpose so he could quip about it.

Unlike modern comics, Rogers wrote his own jokes, whether they were told on stage, in print, or over the air.

The constant need for fresh material gave rise to his signature bit, bringing the day’s newspaper on stage to read in front of the audience while poking fun at the latest headlines. The topical humor naturally gave rise to political humor, the comedic niche for which Rogers became best known.

From vaudeville, Rogers moved on to a starring role on Broadway (The Ziegfeld Follies), movies both silent and sound (he was the top box office star of 1934), best-selling books, a syndicated newspaper column, the most sought-after speaker on the lecture circuit, and the nation’s number one weekly radio show.

With each medium mastered, Rogers lassoed himself a larger audience until he had a higher name recognition among his countrymen at the time of his death than anyone save the president.

Speaking of presidents, Rogers knew every one from Roosevelt to Roosevelt. And he made sport of them all. Here is where today’s comedians should take note, for the approach Rogers took to political humor is as lost an art today as anything he did with a lariat.

Many today wish the current crop of comics would harken back to the days of Jay Leno or Johnny Carson, where political jokes were meticulously doled out as if a bean counter were employed to make sure each side of the political divide had the same number of punchlines.

Granted, the Leno-Carson approach was better than what we have now, both in the tone and quality of the jokes, but that was not the Rogers approach. Leno and Carson had no cogent political philosophy, at least not while on stage. Rogers most certainly did.

Rogers believed in a Jeffersonian populism that sympathized with the average American and sought to advance his interests. He took a dim view of politicians, business tycoons, financiers, moral crusaders, and busybodies. He saw phonies a mile away and feasted on hypocrisy (incongruity being the most common source of humor).

In short, Rogers’ politics were the politics of the great mass of the American people, so much so that he was forced to laugh off repeated suggestions that he run for president in 1924, 1928, and 1932.

But that was only half of what made Rogers great. The other half was his genuine humanity.

“I never met a man I didn’t like,” is his most famous quote. It might not be entirely true, but it is safe to say Rogers never met a man he hated.

He offered a popular political message with ill will towards none, all done with unmatched humor and grace.

Today’s late-night comedians should try it. But it would probably be easier for them to master the lariat than win back an audience.

Paul F. Petrick is an attorney in Cleveland, Ohio.