By Roberta McKern

For The New Era

As usual, the East Linn Museum is closed for the early part of the winter. A cold breeze

swirls around it, but memories of the past remain safe within and we have the

opportunity to borrow a book from the research room.

“Making the Most of the Best,” by Catherine A. Baldwin, published by Willamette Industries, Inc. celebrates the company’s 75th anniversary in 1981. The book is now an irony.

When the company was running full tilt, its employees included around 8,500 men and

women in 14 states and it manufactured lumber, plywood, veneer, particleboard,

pulp, paper, corrugated containers, bags and business forms and folding cartons. It was

a big, integrated corporation, much bigger than most of us know because for our area, it

meant logging, operating sawmills, making plywood, and making wood chips for paper

production.

Having someone related to us who worked there was about as close as we

expected to get to the company.

As it turns out, when we heard talk in our area of logging on Snow Peak or up on

Swamp Mountain or for Santiam Lumber Company, we did not see the connection to

Willamette Industries.

Willamette began logging on Snow Peak in 1939 and in 1941, Snow Peak along with

Black Rock in Polk County, first focus of the company, were declared tree farms. Over

60 years later, we went on a trip sponsored by the company which led us to a stretch

of forest carefully tended to allow growth of endless trees, mostly conifers and bright

healthy green.

As for Santiam Lumber Company, in 1951, Willamette Valley bought an interest in that

enterprise. Willamette Valley tended to sidle up to a company with which it could work

and, by and by, if all went well, Willamette Valley gained complete ownership.

With the purchase of Santiam, Willamette Valley’s name was lengthened to Willamette National

in honor of the national forest behind the Sweet Home area.

They also entered into an agreement with the Hill family who had interests in the Cascades involving holdings associated with the granting of sections of land to railroads to encourage the building of a rail line.

A railroad company could trade its sections for forest owned by the government under a legislative act similar to homesteading, quarter section (160 acres) by quarter section.

Louis Gerlinger, the founder of Willamette, firmly believed in the company’s ownership

of timber land for future development. He often directed his interest in acquisition to

companies and individuals that brought in such lands.

Gerlinger had come to the United States from Alsace-Lorraine (an area of contention sometimes French and sometimes German). Born in 1853, at 17 he immigrated and settled successfully in Chicago.

When he was in his 40s, he travelled west to build a short-line railroad for the Harrimans between Portland, Vancouver and Yakima.

He then purchased 7,000 acres of timber in Polk County in the coast range near Dallas. He planned to harvest the trees and then sell the land to farmers for stump farms.

He built his own short-line railroad and incorporated the Salem, Falls City and Western Railway and raised money from the citizens of Dallas to run a four-mile line into timber country where he

established a logging camp called Black Rock.

Two of his sons operated the railroad, which carried passengers as well as freight, and a

third, George, began running the Fall City Lumber Company. Another enterprising man

built a mill of his own on the edge of Dallas; the Gerlingers bought him out, and the

Willamette Valley Lumber Company was inaugurated, sowing seeds for Willamette

Industries. Gerlinger never sold the Polk County lands.

All did not go smoothly for Willamette. Fires occurred. Unions wanted to organize the

employees. World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II intervened.

Still, the company continued to grow.

But Willamette did more than just persevere; it often prospered, even though it was slapped by a heavy fine for pollution after the Environmental Protection Act went into effect in 1970.

Louis Gerlinger, Sr., died in 1948, but he left a legacy of canny management and

intelligent forethought. He encouraged the diversification of products leading to the

company’s emphasis on making full-use or forest by-products with the manufacture of

such lines as veneers, paper, business forms, and particleboard among other uses. (A

plastic bag manufacturing unit is even listed.)

When Willamette celebrated its 75th anniversary in 1981, all personnel were

feeling pretty good. There was continued hope to gain more acreage in tree farms for

sustainability,

At the time Willamette owned 555,000 acres under extensive management which meant

replanting, fertilizing, and thinning although mother nature had to see to watering.

And the company maintained was a cadre of highly capable leaders and managers,

family members included.

In Willamette’s book, Donald R. Knudsen states the successful rules followed by

company policy.

There are eight:

(1) Fully utilize the forest resources (timber).

(2) Operate plants both continuously and efficiently (keep the machinery repaired).

(3) Provide stable employment to encourage a valued work force.

(4) Make certain customers receive quality products (no substitutions).

(5) Expand only to benefit shareholders.

(6) Stay in lines we know.

(7) Stay in domestic operations as long as opportunities exist (the company already had accounts abroad in Europe and Asia.

And, maybe most important of all,

(8) Adhere to conservative financial practices while relying on internally generated funds for expansion (neither a borrower nor a lender be).

Following these rules, we can now incorporate. This may sound like Economics 101, but

we have must remember that Willamette was feeling very successful.

So, why have we said the company’s success would become an “irony”?

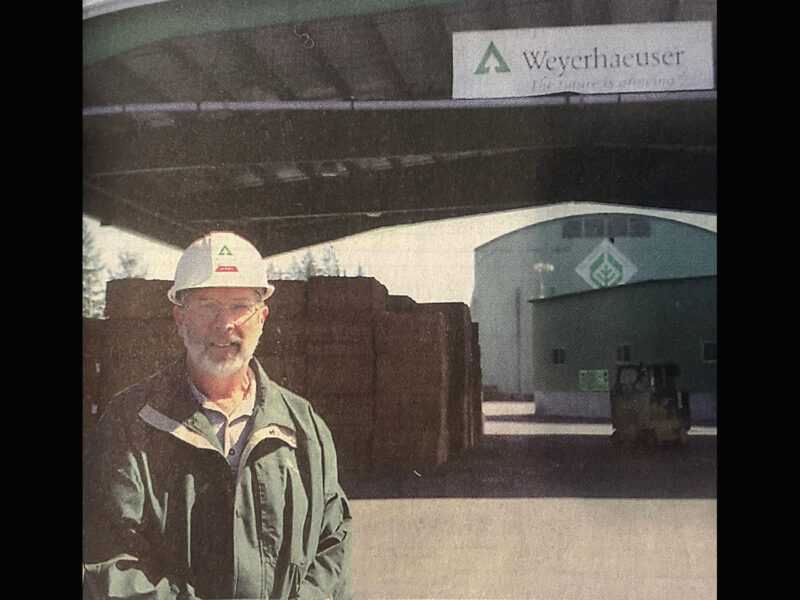

In 2002 Willamette Industries, Inc., was purchased by Weyerhaeuser in a hostile buyout.

Hearsay is Weyerhaeuser’s intent was to gain Willamette’s carefully acquired

timberlands. More extensive than Willamette, Weyerhaeuser had the same desire: to

acquire additional timberlands as a sustained resource, and it had started tree farming even

earlier than Willamette Industries. While it takes decades to grow a crop of trees, time

becomes an investment.

In the East Linn area, there are limited traces of a company once an important

employer here.

The veneer plant at Foster is under new ownership. Other facilities have been

razed. A few long and decaying drying sheds may still be around, but some have been

burned, leaving charred remains.

Willamette took over the Santiam Company’s mill in 1951and at some point after 1976, when the museum was opened, we received the whistle used in that mill.

It is a prized steamboat whistle with three tones – alto, tenor and bass – operating together. It was salvaged from the Terrascone, a packet boat in the Ohio-Kentucky region.

Mill employees of Santiam joined to purchase it and bring it here.

Whether it subsequently operated for the Willamette mills, we do not know. As a

souvenir of the East Linn Museum’s logging industry exhibit, the Willamette Industries

anniversary book, “Making the Best of the Most” is about all we can definitively

recognize. Copies given to Willamette Industries employees could still be somewhere in

the vicinity.

Meanwhile, we can listen to the Terrascone’s steam whistle in remembrance of Santiam and Willamette’s logging days as written about many years ago.

The East Linn Museum opens again in February.

Happy New Year to us all!