Scott Swanson

Of The New Era

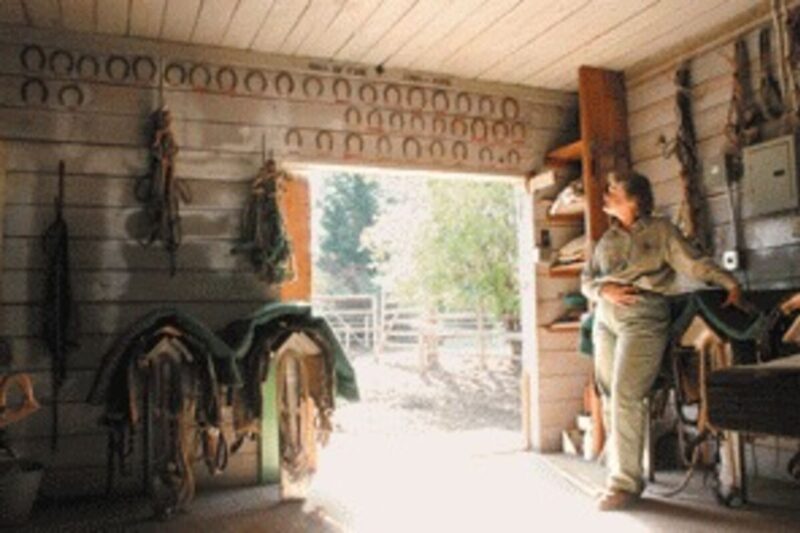

Their names line the wall of the dim tack room: Bob, Rosie, Dusty, Biscuit, Stinger, Babe, Frog, Cindy, Roxy and a couple of dozen others.

They are the mules, and a few horses, who have served with packer Betty Applebaker in the stock packing program headquartered at the U.S. Forest Service Fish Lake Guard Station over the past two decades.

Soon, possibly next summer, there will be no more pack animals at Fish Lake and Applebaker will retire. McKenzie District Forest Service officials have decided to end the pack program at Fish Lake after some 95 years.

“Times are changing, and we’re having to look at more efficient ways of doing things,” said McKenzie District Supervising Ranger Mary Allison , who has been in the Forest Service 30 years and took over at McKenzie 15 months ago.

The move is a result of changing priorities, Applebaker believes. Last year, she said, 14 people worked on the summer trial crew that maintains the 500 miles of trails in the area. This summer there were six, and she said there may be half that next season.

“Budgets have been going down during the last three administrations,” she said. “My feeling is that the wilderness is not a priority any more.”

Applebaker said pack teams have been part of the Forest Service operations since the agency was established in 1905. In addition to Fish Lake, in Oregon and Washington there are stock pack teams in the Okanogon and Wanatchee wilderness areas, two in the Umatilla wilderness, a large pack program in the Wallowa-Whitman district, and a smaller team on the Rogue River.

Acting District Ranger Sandy Ratliff said that it is uncertain whether any stock will be at Fish Lake next summer.

“Right now, we’re starting to transition out of the stock program,” Ratliff said. “By the time Betty retires next year, we will have phased out the stock program.”

Allison said the stock packing program costs “about $60,000 per year,” which she said represents nearly 10 percent of the total forest recreation budget for the Willamette National Forest. The recreation budget includes funding for forest and trail crews, wilderness use, special use administrators, patrol personnel and some program management. The stock budget includes feed, care and tack for the animals, vehicle costs for the truck and trailer needed to haul the stock, and Applebaker’s salary. Allison said that budget figure also includes an assistant packer position, which was not filled this year.

Applebaker, 59, a serious, determined woman who used to be a school teacher in Sweet Home, has run the pack program at Fish Lake since 1985, and until recently, she said, was the only woman in Oregon to run a pack program.

During that time her animals and she have hauled supplies to fire lookouts and trail building and maintenance crews throughout the wilderness areas of the Willamette National Forest.

The biggest beneficiaries of the pack program have been the trails crews, Applebaker said. Her mule teams have hauled fresh food, building supplies and tools to the crews who clear the hundreds of miles of wilderness trails of fallen logs and otherwise maintain them. Over the years, she said, she’s also packed such items as a stove, a refrigerator, firefighting equipment, smoke jumper packs, bathroom equipment and part of a wrecked airplane that went down in the 1970s near the Three Sisters.

One of the stranger loads was the swivel office chair one of her mules packed up to a fire lookout.

“The mule was watching the wheels go round and round out of the corner of her eye,” Applebaker said.

If the pack train is shut down, it will mean that trails crews will be able to do less.

“Things are going to change,” Applebaker said. “(The crews) will still be out there working, but they won’t be able to do the job they’ve done.”

Allison said that trail crews’ tours of duty may be shortened from 10 to five days and they may have to pack “more light-weight food,” and may need to cache tools rather than haul them in and out on trails.

She said officials are considering trying to get help from volunteers, such as Back Country Horsemen of America, a group she says was formed to support maintenance of trails on public lands.

“Where I came from in California (the Sequoia National Forest), they did a huge amount of trail work for us,” Allison said.

Applebaker says she grew up with horses on the agricultural Hawaiian island of Lanai, which has many pineapple plantations. She came to Oregon to attend Pacific University in Forest Grove and She coached track and diving and taught physical education teacher at Sweet Home High School, from 1968 to 1976. Her name was Barcroft in those days.

From Sweet Home, she moved to Hillsborough and was a stay-at-home mom for a while. After a divorce, she moved to northeastern Oregon, where she worked for an outfitter as a river guide and got her introduction to packing.

She started as a part-time packer for the Forest Service in Eastern Oregon, then landed the full-time job at Fish Lake. She now commutes from Klamath Falls, where she lives with her husband Dan.

It’s been a good run, she says. Usually she works a four-day week ? 10 to 12 hours a day. The pack team is generally on the trail two or three days a week, covering eight to 22 miles per day.

“This is the type of job that’s task-oriented, not time-oriented,” Applebaker said.

“I like to do it. I like the beauty and the quiet, being with animals in the back country. The wildflowers this year were just spectacular. I hit it just right in Linton Meadows, up in the wilderness. That’s one of our pretty areas.”

Applebaker said that she hasn’t had a lot of problems over the years with wild animals. She sees bears, along with deer and elk, but she’s never seen a mountain lion on the trail.

“I’m sure they see me,” she said.

Her mule trains are shorter these days than they were when she started and had as many as 18 animals on the trail. Her string dropped down to about 15, then down to 13. Today she has 10 mules, ranging in age from 13 to 27, and two pack horses along with her own horse, Chance.

Applebaker said mules are ideal for use on wilderness trails. A hybrid, the offspring usually of a male donkey and a female horse, a mule is built a little differently than a horse and has the ability to keep its back feet underneath it more effectively than most horses.

Mules also tend to have less excitable personalities than most horses, Applebaker said.

“(Being a hybrid) seems to make them very intelligent,” she said. “I think they’re more steady in tough situations. When something’s going on, they don’t go ballistic like horses sometimes do.”

Mules, she said, also have “a real strong sense of self-preservation.

“They want to look at a situation before they do something,” she said. “That’s smart. It used to be interpreted as stubborn.”

Applebaker said she has found that mules will do almost anything for her ? once they trust her.

“You can tell a horse to do something. You have to ask a mule to do something.”

And, frankly, handling mules isn’t that different from teaching.

“They’re fun,” she said. “They’re just like little kids. Bickering, squabbling, carrying on.”

Mules can pack about 15 percent of their body weight, which generally averages around 1,000 pounds for Forest Service pack animals. The load, plus the pack saddle, means each mule carries about 200 pounds.

Her only really bad accident in 20 years on the trail might have been worse if there had been horses involved. Arriving at a camp to pack out trail-building materials, she found that she was going to have to carry two 5 or 6-foot-long cross-cut saws, one without handles. Having no rope for the purpose, she had to improvise. She used the end of the lash rope, which ties the mules in the pack train together, to tie one end of the saws to the pack saddle on one of her mules, then used some parachute cord from the tents to tie the other ends.

The nylon parachute cord, which had been exposed to the sun all summer, wasn’t up to the strain of securing the saws, which had been bent over the top of the pack saddle. About a mile from the trailhead, the cord broke and the saws sprang off the saddle, the guard came off the blades, and they inflicted some puncture wounds on the mule and flopping all over the place as Applebaker tried to get the mules calmed down and grab the saws.

“Since then I’ve made darn sure I have rope with me when I go out,” she said.

In 20 years, she’s only lost one animal on the trail ? a horse.

In addition to being a boon to trails crews, the pack animals are great for the Forest Service’s image, Applebaker said. Years ago, her mules appeared in Portland’s Rose Parade, where they were a big hit and won awards, she said.

“The (public relations) value isn’t appreciated,” she said. “A lot of people don’t like the Forest Service but they like animals.”

One benefit is that she has more rapport with horseback campers, riders and hunters she meets in the wilderness, over rangers on foot.

“It give credibility when you talk to horse users out there,” she said. “When you’ve got some 20-year-old in college who goes out to talk to a 60-year-old about how to take care of a horse, there’s not as much credibility as there is when (the ranger’s) on horseback.”

The pack train also helps relations with people who don’t like horses in the backcountry, period.

“I run into people who don’t like horses out there,” Applebaker said. “When they see us packing the garbage out, it changes their whole demeanor for hating horses because they poop on the trail.”

When the Fish Lake program ends, Applebaker said the mules in her team will go to the Wallowa-Whitman depot in Enterprise, where they winter each year. Two are retiring, including the oldest, Roxy, who will go live with her veterinarian, Tony Otto of Bend.

There’s talk of turning the Fish Lake depot into a museum.

“Lots of people say this is Bush’s fault,” Applebaker said. “I don’t agree. It’s been going on for years.

“The whole wilderness program is suffering. You can’t quantify the value of wilderness, and that’s part of the problem of justifying how much you’re going to spend on it.”

She paused in the dim tack room and looked out into the bright sunlit corral.

“You can intellectualize this (decision), but it’s really hard to take the emotion out of it,” she said, as she looked at her stock, swishing their tails lazily on their day off.

“I’m hoping that as budgets go up and down, as they come back, (the Forest Service) will have wilderness rangers on horseback again.”

But it looks like the end of the trail is nearing for Applebaker.

“Right now, I don’t know what to do,” she said, gazing at the rough plank floor. “I may retire this winter, or I may come back for one more year.”

Allison said the decision to eliminate the stock packing program has been made with reluctance.

“(Betty’s) done an incredible job,” Allison said. “It’s a great program. If we had funding, we would continue to support the program. All of us have a little tear in our eye over the whole thing.”